Introduction

Black fashion designers work in a broad range of styles, expressing individual ideas, emotions, and attitudes. Some draw from their African diasporic heritage, while others work in a western fashion tradition. Still others combine all manner of inspiration, construction techniques, and aesthetics. Each one approaches design from a unique perspective, and it is that diversity which most enriches fashion.

-

Image InfoClose

Introduction Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Ann Lowe Wedding Dress (Left) Silk peau de soie, 1968, USA, 2009.70.2 , gift of Judith A. Tabler

Ann Lowe learned her craft from her grandmother, a former slave in Alabama. She became famous among the wealthy American elite of the 1950s and 1960s for her couture-quality gowns. Based in New York, Lowe specialized in debutante and wedding dresses, such as this gown that she custom-made for Judith Tabler.

Amsale Wedding Dress (Right) Silk, sequins, beads, bugle beads, fall 2016, USA, 2016.107.1, gift of Amsale.

In 1985, Amsale Aberra began her global bridal and eveningwear brand, Amsale, with her own wedding dress. This hand-embroidered gown exemplifies the luxurious, sophisticated, and modern style that Amsale represents.

-

Image InfoClose

Laura Smalls Dress (Left) Cotton blend jacquard, spring 2016, USA, 2016.90.1 , gift of Laura Smalls

Laura Smalls brings decades of experience at major fashion companies to her sophisticated label. Impressed by her flattering designs, André Leon Talley encouraged Smalls to show at New York Fashion Week in 2009. Smalls’s devoted clientele includes Michelle Obama, who famously wore this red floral design on The Late Late Show with James Corden.

Loomia by Madison Maxey (Right) Hemp, recycled computer and headphone cords, 2016, USA, 2016.84.1, gift of Madison Maxey.

Creative technologist Maddison Maxey embraces both sustainability and technology as the future of fashion. For this dress, Maxey used computer code to generate the print and collaborated with natural dyer and textile artist Nica Rabinowitz to execute it. The materials are sustainable and recycled, and the dress was cut with a zero-waste pattern.

-

Image InfoClose

Patrick Kelly Dress (Left) Wool, plastic, fall 1986, USA, 2016.48.1 , museum purchase

Patrick Kelly used mismatched buttons in his designs in homage to his grandmother (“one of the chicest women I know”), who mended the Kelly family’s clothing. Kelly recounted to journalist Bonnie Johnson, “to detract from having to use mismatched buttons on his shirts, she started sewing them everywhere.”

Duro Olowu Ensemble (Right) Cotton and silk lace, silk charmeuse, wool and silk crepe, fall 2012, England, 2016.65.1, gift of Duro Olowu.

Duro Olowu’s international success arises from “a strong visual cross-cultural aesthetic, quality of the cut and the fabric, and an appreciation for the female form.” Olowu masterfully embraces bricolage, vibrantly mixing colors, prints, and textures.

Breaking into the Industry

The New York fashion industry of the 1950s was, in practice, segregated. By 1960, some black designers had begun to learn the business while working for Seventh Avenue manufacturers, and soon struck out on their own to found namesake brands. Jewelry designer Bill Smith suggested that such autonomy was essential: “You have to make money in order to be creative, to have the freedom to be creative.” During the 1980s, designer Willi Smith built a lucrative international sportswear brand and was often compared to his contemporary, Calvin Klein. Today, a new generation of black designers is finding success in high fashion.

-

Image InfoClose

Breaking into the Industry Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Jon Weston Dress

Silk, 1955, USA, 2016.78.7, gift of Audrey Smaltz.Jon Weston attended FIT and designed this gown for his 1955 graduation show. Audrey Smaltz modeled it, then wore it again in a 1961 Ebony advertisement. Weston struggled with fashion industry discrimination and had financial difficulties during the 1960s, but persevered to establish a successful studio on Seventh Avenue by the 1970s.

-

Image InfoClose

Harbison Coat

Wool, spring 215, USA, 2016.58.1, gift of Harbison.Designer Charles Harbison drew on his background of fine arts and architecture for this classic double-breasted coat, which is divided by a red sash and powder-blue insets into geometric blocks of color. Harbison was one of the few designers invited to speak at Michelle Obama’s Fashion Education Workshop at the White House.

-

Image InfoClose

Williwear Pantsuit

Cotton, cotton knit, circa 1984, USA, 2013.52.4, gift of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA).Willi Smith founded Williwear in 1976 with partner Laurie Mallet. He soon established a reputation for fun and accessible sportswear – like this multi-stripe suit. Women’s Wear Daily reported that “the company went from $30,000 in sales the first year to $5 million the second.” Smith opened stores in New York, London, and Paris.

African Influence

High fashion often appropriates elements of African culture for inspiration – frequently with little understanding or sensitivity. Inspired by their own heritage, black designers tend to take a more nuanced approach, celebrating the distinctiveness of particular African aesthetic traditions. Bricolage and improvisation are two techniques that unite many African art forms, exemplified by the designs in this section. Black designers also sometimes reference Africa’s historic role as a global center of textile and arts production.

-

Image InfoClose

African Influence Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Patrick Kelly Leggings and hat (Left) Spandex, straw, cotton, spring 1988, France, 98.90.2, 2016.82.17, gift of Ms. Julia Szabo, Gift of Bjorn G. Amelan and Bill T. Jones.

Patrick Kelly references Ghanian kente cloth in this ensemble, replicating the woven pattern as a print. Reproducing a traditional pattern on contemporary fashion might read as appropriation. But those familiar with Kelly’s work know he consistently celebrated blackness by embracing controversial iconography with joyful wit.

Stella Jean Dress and socks (right) Cotton, fall 2015, Italy, 2015.4.2, gift of Stella Jean.

“I’m keen to discover fabrics that people think are produced in a particular location and show them it’s actually a different story altogether,” said designer Stella Jean. Wax prints are often referred to as African fabrics, but in fact are appropriated from African culture and made in Holland. This dress with sharp Italian tailoring incorporates wax prints Jean commissioned from African artisans in Burkina Faso.

-

Image InfoClose

Nigerian designer Lisa Folawiyo is known for modernizing and embellishing Ankara, a West African fabric, using her own custom prints and embellishments. The Dutch developed Ankara to mimic 16th century Javanese batik, and West Africans adopted it into their dress, starting in the 19th century. Folawiyo’s international appeal today reestablishes Ankara’s historical roots.

Lisa Folawiyo Dress (Left) Cotton blend, glass, spring 2015, Nigeria, 2015.6.1, gift of Lisa Folawiyo.

Mimi Plange Dress (Middle) Leather, spring 2013, USA, 2016.49.1, gift of Mimi Plange.

Christie Brown ensemble (Right) Cotton, synthetic ,spring 2016, Ghana, 2016.54.1, gift of Christie Brown.

-

Image InfoClose

Stella Jean and Christian Louboutin Boot

Cotton, fall 2015, Italy, 2015.4.5, gift of Stella Jean.

Rise of the Black Designer

In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, American society was increasingly responsive to African American cultural forms, most notably in music. As black singers popularized disco, black designers, working in a sexy, disco-influenced style, made a significant impact on New York fashion. The success of black designers during the 1970s alerted the fashion industry to their talents – and the door slowly began to open for a few of them to find success leading large fashion houses, such as Burberry in London, Paco Rabanne in Paris, and Lafayette 148 in New York.

-

Image InfoClose

Rise of the Black Designer Iinstallation View

-

Image InfoClose

James Daugherty Jumpsuit (Left) Polyester matte jersey, circa 1974, USA, 92.106.1, gift of Leslie Fay Evening

James Daugherty designed sultry, disco-era garments, such as this green jumpsuit, that Ebony called “sizzlers.” He began his career designing Hollywood costumes for Edith Head, worked in New York throughout the 1960s, and then established his own brand in 1974. Daughtery designed on Seventh Avenue through the 1990s, and was a professor at FIT.

Jon Haggins Dress (Right) Silk, 1980-1985, USA, 2016.89.1, museum purchase.

In 1966, Jon Haggins defied the popular trend for structured clothes, founding his company on soft, sinuous designs that foresaw the disco era. In 1968, Bernadine Morris of the New York Times wrote, “He’s gaining recognition for the right reasons – his designs, not his race” (though his race did not go without saying).

-

Image InfoClose

Paco Rabanne (Patrick Robinson) Dress and jacket (Left) Silk, cotton, swan feathers, spring 2006, USA, 2016.88.1, gift of Virginia Smith

Designer Patrick Robinson constructed this royal blue dress from vintage silk kimonos. In a manner similar to Paco Rabanne, Robinson pieced material together – seen in the side slits – to create a unique design. Robinson has played an instrumental role in reviving the legacy of not only Rabanne, but also brands such as Anne Klein, Perry Ellis, and Armani White Label.

Balmain (Olivier Rousteing) Dress (Right) Raffia, silk, rhinestones, spring 2013, France, 2016. 106.1, gift of the House of Balmain.

Olivier Rousteing personally selected this design for this

exhibition, “When the craziness meets craftsmanship,” he explained, “that is what I call couture.” The open work detail on this dress was created from hand-woven raffia and was inspired by traditional Cuban wicker chairs. Rousteing says that when he was appointed creative director of Balmain at 26, people were shocked not by his age, but his color. -

Image InfoClose

Stephen Burrows Top and pant (Left) Lamè, circa 1977, USA, 79.187.26, gift of Ethel Scull.

Scott Barrie Dress (Middle) Rayon jersey, circa 1973, USA, 81.145.3, gift of Naomi Simms.

Fabrice (Right) Jumpsuit: Rayon crepe , circa 1978, USA, P90.19.1, museum purchase.

Jacket: Silk crepe, sequins, bugle beads, pearls, early 1980s, USA, 2016.78.7, gift of Audrey Smaltz.Fabrice Simon commissioned embroiderers from his native Haiti to create beaded eveningwear that was a hit among celebrities, such as Whitney Houston. “He painted with beads,” said former associate Alice Katz. Fabrice, as he preferred to be called, was inspired by modern artists such as Jean Miró.

Eveningwear

During the 19th century, black dressmakers created luxurious eveningwear for elite women. Today’s black designers continue this tradition, creating custom pieces for a celebrity clientele. Bruce Oldfield, for example, became famous for his designs for Princess Diana, and LaQuan Smith has dressed Beyoncé.

Each impeccably crafted dress in this section represents a different luxury technique, from the intricate beading on Eric Gaskins’s gown to the brocade fabric used in B. Michaels’s cocktail dress. Several of these designers’ creations have caught the eye of exclusive retailors, such as Bergdorf Goodman, and are often featured in Fifth Avenue windows.

-

Image InfoClose

Eveningwear Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

LaQuan Smith Dress, (Left) Cotton lace, fall 2016, USA, 2016.51.1, gift of LaQuan Smith.

Lawrence Steele Dress (Middle) Synthetic knit, Swarovski crystals, spring 2002, Italy, 2016.62.1, gift of Lawrence Steele.

Rubin and Chapelle Dress (Right) Nylon, silk charmeuse, wool blend jersey,fall 2012, USA, 2014.5.1, museum purchase.

Sonja Rubin and Kip Chapelle, alumni of FIT, partnered in 1997 to launch their brand Rubin and Chapelle. They created this dress as an alternative to black tie and replaced traditional white accents with gold. Breaking from their classic draped designs, they contoured the dress using girdle inset side panels.

-

Image InfoClose

Ann Lowe Dress (Left) Silk velvet, circa 1955, USA, 77.60.1 , gift of Eleanor Cates.

This dress illustrates Lowe’s mastery of fine dressmaking, incorporating an intricate understructure to shape the hourglass silhouette. Ebony magazine noted in 1966, “She is famous for her expensive hand-sewn formal gowns, each so superbly constructed and fitted with built-in bras that the wearer just steps into one and is ready to go.”

B. Michael Dress (Right) Silk brocade, fall 2005, USA, 2016.30.1, gift of b. michael AMERICA.

“It’s definitely about classic American style,” B. Michael says. His elegant, feminine designs, popular with many celebrities, include this dress worn by singer Brandy. On being identified as a black designer, he stated, “Subjectively, it’s important that I am embraced for who I am…but…my work is about being an American designer.”

-

Image InfoClose

CD Greene Dress

Nylon net, Swarovski crystals, 1996, USA, 2016, CD Greene.Bergdorf Goodman was an early supporter of CD Greene and first featured his designs in its June 1990 windows. In 1996, Greene was commissioned to create Tina Turner’s wardrobe for her Wildest Dreams tour. For this mini dress, he selected a sheer white net and Swarovski crystals to contrast with Turner’s skin, so that she would stand out on stage.

-

Image InfoClose

Eric Gaskins Dress

Silk, glass beads, 2014, USA, 2016.53.1, Eric Gaskins.Eric Gaskins trained as a fine artist and apprenticed with Hubert Givenchy before establishing his company in 1987. This gown’s meticulous beading captures the brushwork of one of his favorite artists, Franz Kline. Elegant eveningwear such as this exemplifies Gaskins’s aesthetic of simple lines coupled with rigorous cut and extraordinary details.

-

Image InfoClose

Cushnie et Ochs evening top and skirt

Viscose blend, fall 2005, USA, 2016. 67.1, gift of Cushnie et Ochs.The bold cut-outs on this two-piece dress are balanced with a maxi skirt. Design duo Carly Cushnie and Michelle Ochs have said that when they started their company, they “felt there wasn’t clothing out there for a sophisticated woman who wanted to be sexy without being vulgar.” Their first collection was immediately successful, and was picked up by Linda Fargo of Bergdorf Goodman in 2009.

Street Influence

During the late 1980s, oversized styles were popularized by hip hop artists and inner-city youth in New York. They influenced a new category of fashion brands, such as Cross Colours, that were led by black owners. These styles appealed to an untapped market and surprised the industry – which then began to appropriate street styles while rarely giving credit to the originators. More recently, brands such as Off-White and Public School have been infusing high fashion with hip hop and street culture. They are subverting assumptions about street-influenced fashion, leaving journalists unable to categorize their style.

-

Image InfoClose

Street Influence Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Off-White Ensemble (Left) Wool, cotton, denim, suede, fall 2015, Italy, 2016.95.1, gift of Off-White c/o Virgil Abloh.

The ropes on the jacket and boots of this ensemble were inspired by vintage mountaineering equipment and street style. Designer Virgil Abloh uses rope as a metaphor for climbing the corporate ladder. “Streetwear is seen as cheap,” he says. “My goal is to add an intellectual layer to it and make it credible.” Abloh chooses to identify his customer as neither black nor white, and so he calls his brand Off-White.

Public School Ensemble (Middle) Silk, rayon, wool, cotton, leather, metal, fall 2016, USA, 2016.64.1, gift of Public School NYC.

Designers Maxwell Osborne and Dao-Yi Chow of Public School envisioned a woman trekking through post-apocalyptic New York City streets for their fall 2016 collection. In this ensemble, utilitarian elements such as a beanie with a chain link detail are juxtaposed with an elegant fringe knit vest. “We start from a street base, but our influences are high fashion,” says Chow.

-

Image InfoClose

XULY.Bët Ensemble

Cotton with applied metallic pattern, faux fur, synthetic stretch suede, fall 2016, France, 2016.16.1, gift of Xuly.Bët.Since 1991, Parisian designer Lamine Kouyaté of XULY.Bët has been using the street as both inspiration and performance space. In 2015, he staged a guerrilla show in New York. Kouyaté utilizes the subversive street setting to counterbalance his commercial success, separating his defiantly attention-grabbing designs from the fashion establishment.

Menswear

In the late 1970s, Andrew Ramroop became the first black tailor to work on London’s Savile Row, and black menswear designers in New York were building successful businesses. Jeffrey Banks worked within the American preppy style, mixing traditional tweeds with colorful twists. Black sportswear designers, such as Willi Smith, offered casual cotton ensembles in brilliant prints. During the 2000s, lavish suits fit for a dandy made a return on the Sean John runways. Younger British designers are currently pushing the boundaries of tradition. While maintaining a high standard of tailoring, they are experimenting with proportion, design concepts, and ideas of masculine identity.

-

Image InfoClose

Menswear Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Sean John Man’s ensemble (Left) Wool, cotton, fur, silk, fall 2008, USA, 2016.96.1 , gift of Sean John.

Founded in 1998, Sean John merged hip hop style with high fashion, inspiring later designers, including those at Vetements, Balenciaga, and Yeezy. In 2004, Sean Combs became the first black designer to win a CFDA award. He reflected: “Being an African American designer was very heavy on my heart…People tried to put us in a little box. . . . The CFDA award changed the perception.”

Maurice Sedwell (Andrew Ramroop OBE) Suit (Middle) Silk/wool blend, 2003, England, 2016.56.1, gift of Maurice Sedwell (Savile Row).

Trinidad-born tailor Andrew Ramroop apprenticed under Maurice Sedwell and purchased Sedwell’s Savile Row firm in 1988. This bespoke suit was completely hand cut and tailored by Ramroop in his signature delta style, which is characterized by an inverted V-shape hem. In 2008, Ramroop founded the Savile Row Academy to train a new generation of bespoke tailors.

Wales Bonner Man’s suit (Right) Wool, cashmere, viscose, spring 2017, England, 2016.86.1, museum purchase.

Grace Wales Bonner has received many accolades, including the prestigious LVMH prize in 2016, for her subversive and cerebral menswear that challenges stereotypes of aggressive black masculinity. This gold-and-crystal embellished suit was inspired by the crowning of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie in 1930. It manifests Wales Bonner’s signature “hybridity” by blending European, African, and Caribbean references.

-

Image InfoClose

WilliWear Man’s ensemble (Left) Cotton, ramie-cotton knit, spring 1985, USA, 85.71.1 , gift of WilliWear, Ltd.

Willi Smith expanded into menswear in 1982, bringing his signature “street-smart, witty” styles to a new demographic. His whimsical sense of color and pattern is shown in this ensemble. Smith intended to be a painter, but his family’s love of fashion and a summer job as a teenager on Seventh Avenue redirected him to design.

Jeffrey Banks Man’s ensemble (Right) Wool tweed, cotton velveteen, cotton, circa 1981, USA, 2016.79.1, gift of Jeffrey Banks.

Jeffrey Banks has had a long and respected career in American menswear. In 1982, the New York Times said, “Mr. Banks…makes clothing that is simply exceptional,” pointing to the fine quality of his fabrics and his adventurous use of colors, both of which are seen in this innovative, yet classic suit.

-

Image InfoClose

Casely-Hayford Ensemble (Left) Synesthetic, acrylic, wool & alpaca blend; wool, leather, fall 2015, England, 2016.57.2 , gift of Casely-Hayford.

Father-son design duo Joe and Charlie Casely-Hayford begin their menswear design process with an exchange of ideas from which they develop a thesis that balances their opposing aesthetics. The parka and mohair sweater in this ensemble reference the layered look of runaways, and deliberately contrast with the sophisticated tailoring of the trousers and shirt.

Agi & Sam Man’s ensemble (Right) Wool, rayon, cotton, Velcro, fall 2015, England, 2016.66.1, gift of Agi & Sam.

Agi Mdumulla and design partner Sam Cotton are shaking up traditional British menswear with quirky, imaginative designs. This suit’s inspiration came from a collection that Mdumulla designed at age four (the drawings were safeguarded by his mother). The design duo also consulted focus groups of children, resulting in a playful, pull-apart Velcro suit and primary-colored knits.

-

Image InfoClose

Byron Lars Dress (Left) Cotton, silk, fall 1991, USA, 91.204.1 , gift of Byron Lars.

This tailored wrap dress by Byron Lars is a twist on a man’s classic Oxford shirt. Buyers at Bloomingdales were amused by its witty design and featured the dress in their fall 1991 ad campaign, photographed by Steven Misel. That same year, Women’s Wear Daily named Lars “Rookie of the Year.”

Patrick Kelly Ensemble (Right) Cotton denim, spring 1989, France, 2016.103.1, museum purchase.

This ensemble accented with playing dice exemplifies the sense of humor at the heart of Patrick Kelly’s designs. Bernadine Morris of the New York Times said, “The clothes are good, but what matters most is the joyful spirit the designer projects. He seems to have fun making clothes, and his models look happy showing them.”

-

Image InfoClose

Patrick Kelly sunglasses Plastic, metal, spring 1989, France, 98.159.43, gift of Ady Gluck-Frankel

Black Models

Before the 1960s, black models were rarely featured in magazines, other than Jet and Ebony. But on the heels of the Civil Rights Movement, “Black is Beautiful” became a rallying cry, and black models broke into the mainstream. Leading fashion photographers such as Richard Avedon and Irving Penn captured their beauty for the pages of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.

Black models were important during the 1970s as muses to designers, such as Scott Barrie and Stephen Burrows, and to Azzadine Alaia in the 1990s. In 2008, with the election of Barack Obama, diversity became a focus in fashion, spawning various articles on black models. Yet black runway models remain more an exception than a standard.

-

Image InfoClose

Black Models Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Scott Barrie Dress (Left) Synthetic jersey, 1971, USA, 2016.78.3 , gift of Audrey Smaltz.

Audrey Smaltz wore this Scott Barrie gown as commentator for the Ebony Fashion Fair in 1971. The touring show of haute couture and high fashion was established in 1958 as one of the only platforms available for black models. Smaltz, remembered as the fair’s most entertaining announcer, accompanied director Eunice Johnson to Paris to purchase the haute couture.

Stephen Burrows Ensemble (Right) Silk satin, 1977, USA, 81.145.15, gift of Naomi Sims.

This ensemble was worn by model Naomi Sims, who was fond of white because it highlighted her dark complexion. Designer Stephen Burrows recalls the first time he saw Sims, “She emerged…looking like the most beautiful woman I had ever seen…and would inspire future icons such as Pat Cleveland and Alva Chinn.” Burrows constructed these pants in the shape of a petal by wrapping silk satin around the legs.

-

Image InfoClose

Stephen Burrows Top and skirt

Silk chiffon, 1973, USA, 99.15.1, gift of Mrs. Savanna Clark.The “lettuce” hem on this dress was created by mistake, when Stephen Burrows’s assistant overstretched a jersey hem. “I liked the look of it,” Burrows said. He made it his signature element. This tiered silk chiffon ensemble was featured in the famous “Battle of Versailles” fashion show, which catapulted his career onto the international stage.

-

Image InfoClose

lemlem by Liya Kebede Dress

Cotton, spring 2014, Ethiopia, 2016.59.1, gift of Liya Kebede.Supermodel and World Health Organization ambassador Liya Kebede founded lemlem in 2007 in her home country of Ethiopia. Lemlem means “to bloom” or “to flourish” in Amharic, and it captures Kebede’s mission to sustain both traditional weaving and economic prosperity through modern fashion. Ethiopian weavers created the intricate fabric of this dress by hand.

-

Image InfoClose

Veronica Webb styled this ensemble to represent the designers whose fashions she modeled throughout her career. The body contouring bustier and knit pants by Tunisian-born, Paris-based designer Azzedine Alaïa are balanced with the sculptural curves of a Comme de Garçons jacket. Webb’s closest working relationship was with Alaïa, who included her at each step of the design process.

Comme des Garçons Jacket Canvas and metal (zippers), fall 2006, Japan, 2008.65.3, gift of Veronica Webb.

Azzedine Alaïa Bustier Rayon and Polyamide stretch knit blend, fall 1991, France, 2013.25.7, gift of Veronica Del Gatto.

Azzedine Alaïa Pants Wool knit, 1984, France, 2008.65.9, gift of Veronica Webb.

Pierre Hardy Shoes Metallic leather, leather, suede, 1990s, France, 2009.71.4, gift of Veronica Webb.

Activism

There is a rich history of activism and protest in black communities all over the world. Fashion has long been a part of progressive political movements, from reviving traditional textiles to wearing Afro hairstyles. Black designers often use fashion as a form of personal communication, to speak out on crucial issues. By voicing opinions and supporting important causes, the designers seen here tap into that tradition, adding their own perspectives and aesthetics. They empower the people who wear their designs, providing outlets for frustration and anger, as well as hope for the future.

-

Image InfoClose

Activism Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Stoned Cherrie T-shirt and Tsonga skirt

Cotton blend knit, cotton, polyester, metal, 2010, South Africa, 2016.70.1, gift of Stoned Cherrie.A self-proclaimed “creative activist,” Nkhensani Nkosi of Stoned Cherrie evinces South African political nostalgia and black consciousness in this ensemble by pairing a Drum T-shirt with a traditional, and distinctly South African, Tsonga skirt. Drum was popular in the mid-20th century for its celebration of black culture and discerning coverage of the emerging anti-apartheid movement.

-

Image InfoClose

Patrick Kelly Brooch

Plastic, 1987-1990, France, 2010.30.4,, gift of Gloria Steinem.Patrick Kelly gave black baby brooches to friends and as fashion show favors. His partner, Bjorn Amelan believes that Kelly’s use of controversial imagery stemmed from racism he experienced while growing up. “Rather than cower and try to repress that, [Kelly found] the most effective way to deal with it was to appropriate and send back that image in an empowered way.”

-

Image InfoClose

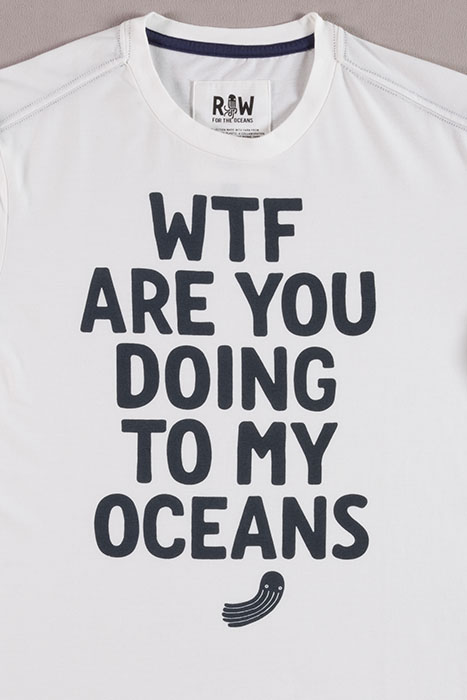

G-Star RAW T-shirt

Bionic Yarn from recycled ocean plastic, spring 2016, Netherlands, 2016.71.1, museum purchase.Musician Pharrell Williams is a passionate environmental activist. He co-founded and acts as creative director of Bionic Yarn, a company that recycles plastic waste from the oceans into fabrics, such as the one used to create this T-shirt. After two years of collaborating with Dutch clothing brand G-Star RAW, Pharrell became its co-owner in 2016.

-

Image InfoClose

Pyer Moss Man’s ensemble

Cotton and synthetic blend, fall 2015, USA, 2016.83.1, gift of Pyer Moss.Kerby Jean-Raymond established Pyer Moss in 2013, elevating athletic gear and uniforms into luxury sportswear. Although for this collection he took inspiration from the 1990s streetwear brand Cross Colours, Pyer Moss is not streetwear. Of the frequent miscategorization by journalists, Jean-Raymond asked, “I just want to know what’s being called ‘street,’ the clothes or me?”

-

Image InfoClose

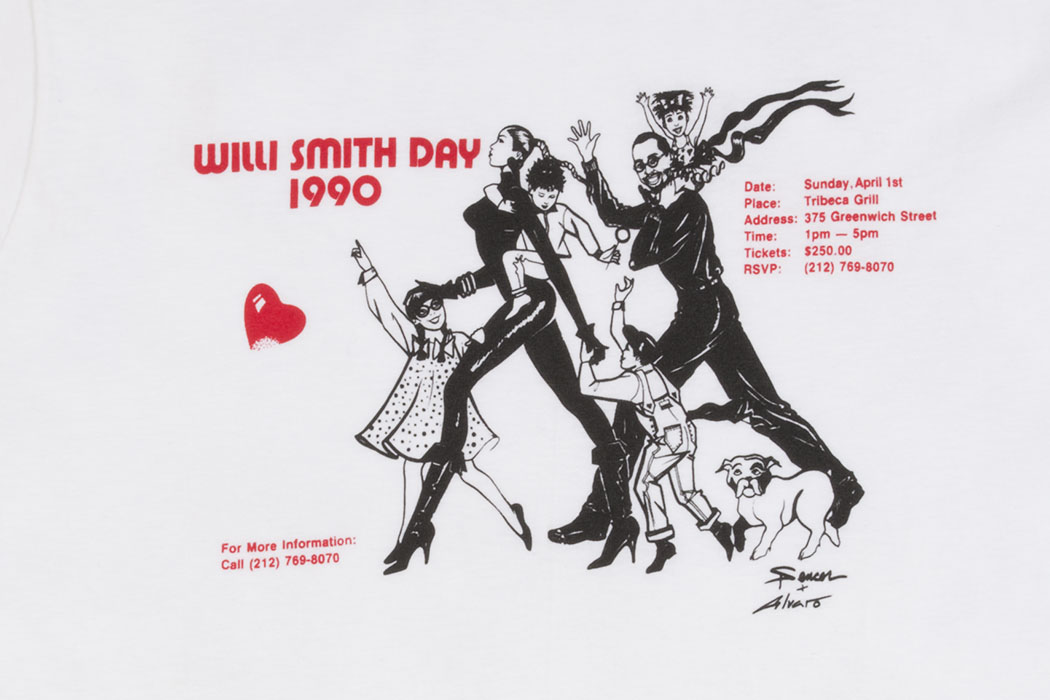

Willi Smith Day T-shirt

Cotton knit, 1990, USA, 90.56.12, gift of Matthew Olszak.Willi Smith died of AIDS in 1987. The next year, Manhattan borough president David Dinkins proclaimed February 23 to be Willi Smith Day, in honor of Smith’s “significant achievement in the fashion world.” He was a quintessential New York designer, taking inspiration from street styles and Harlem church ladies. He aimed to design clothes for “real people.”

Experimentation

The designers in this section create experimental fashions that diverge from mainstream styles to challenge what fashion can be. Some use historic or commonplace techniques, like macramé or pleats to create new silhouettes. Others dissect and re-proportion classic garments, like a shirtdress or a man’s suit, or they reconsider typical materials and introduce surprising elements. Avant-garde design is meant to be bold, and it is not for everyone, but it helps move fashion forward.

-

Image InfoClose

Experimentation Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Jon Weston Coat (Left) Faille, circa 1957, USA, 2016.78.1, gift of Audrey Smaltz.

Jon Weston was known for his evening gowns and for outfitting beauty pageant contestants, including Miss America in 1973. This late-1950s, pleated evening coat is a departure from the popular hourglass silhouette seen in his other work. It is an innovative design, standing away from the body, much more reflective of contemporary Parisian couture silhouettes.

Brenda Waites Bolling Tunic (Right) Silk cord, 1970s, USA, 2016.78.4, gift of Audrey Smaltz.

This custom tunic was handmade using macramé, a knotting technique that dates back to the 13th century. Designer Brenda Waites Bolling said, “I feel the technique I use in my collections offers a new dimension.” Her macramé pieces were purchased by other designers such as Mary McFadden to integrate into their designs.

-

Image InfoClose

Byron Lars Union suit (Left) Linen knit, plastic, wood, 1987, USA, 2010.49.1, gift of Byron Lars.

This clever design gives the illusion of a union suit being suspended by clothes pins from the body, but it is actually attached to a structured bodice underneath. “I was a bit obsessed with trompe l’oeil suspension in the late eighties,” says designer Byron Lars, who was known for his witty creations.

And Re by Andre Walker Ensemble (Right) Cotton, spring 2016, England, 2016.68.1, museum purchase.

Self-taught designer Andre Walker said, “I was never afraid to come up with an idea that was totally impossible.” This ensemble is an abstraction of a classic khaki suit. It embodies what The New York Times describes as Walker’s “near telepathic ability to read the spirit of the moment.”

-

Image InfoClose

Epperson Dress (Left) Unbleached cotton, cotton twine, circa 2008, USA, 2010.49.1, gift of Epperson.

Designer Epperson takes a deconstructed approach to fashion. Here he used unbleached muslin—a material typically reserved for samples—thoughtfully draping, tucking, and gathering the fabric around the body to create a romantic dress. Fashion historian Patricia Mears observed, “Cables become a poetic element in the hands of Epperson.”

Joe Casely-Hayford Ensemble (Right) Wool, synthetic, cotton, horse hair, leather, fall 2000, England, 2016.57.1, gift of Joe Casely-Hayford.

“I was always classified as a ‘black designer,’ so I had to struggle to work against that. I was into punk, I made clothes for The Clash,” said designer Joe Casely-Hayford. His designs juxtapose refined British tailoring with a punk attitude. This tension is represented here in a tailored all-in-one vest, jacket, and coat – paired with an unconventional muslin horsehair skirt.

-

Image InfoClose

Steven Cutting Jacket and pant (Left) Leather, silk, 2016, USA, 2016.94.1, gift of Steven Cutting.

Steven Cutting’s design philosophy of fit, fashion, and function guided his design of this ensemble. The silk iridescent ruffles on the leather jacket provide a delicate, fashionable accent to the hard structure of both the jacket and the pants. Before becoming an FIT professor, he worked for brands such as Krizia, Perry Ellis, and Beyoncé’s House of Dereon.

Hood By Air Ensemble (Right) Nylon, synthetic blend, calfskin leather, 2016, USA, 2016.87.1, gift of Hood By Air.

The Pilgrims of early America and issues of immigration inspired Shane Oliver to create this ensemble, worn on the runway by a male model. Journalist Susie Lau observes that these “references to colonial pillaging and flailing bodies” are connected to “the current tense atmosphere that we live in, with heightened fears of terrorism and divisions of race, geography, and power.”