Halston: The Inspiration of Madame Grès

- By The Museum at FIT

- In General

- On 10 Mar | '2015

This week we’re thrilled to share curatorial insight on Halston and Madame Grès, from co-curator + MFIT deputy director Patricia Mears. For more information on the two designers, check out the essays in the book Yves Saint Laurent + Halston: Fashioning the 70s, as well as Patricia’s book Madame Grès: Sphinx of Fashion. See more from Patricia in our full list of past publications.

Patricia Mears | photo by William Palmer

____________________________

Two of the greatest fashion creators working during the second half of the twentieth century were Madame Alix Grès (1903-1993) and Halston (1932-1990). Although they were of different generations and nationalities, during the 1970s Grès and Halston shared a remarkably similar aesthetic. Each produced unique versions of caftans and evening dresses that were innovatively constructed, comfortable, and sophisticated—attributes that have given their work a timeless quality.

I argue that Halston aligned himself with Grès, the venerated Parisian couturière, soon after his remarkable move from milliner to dressmaker. Although the only known period statement to make a connection between the two designers was penned by fashion journalist Eugenia Sheppard in 1978—when she wrote that Halston could “handle scissors more expertly than almost anyone but Madame Grès”—viewing their designs side-by-side reveals that such an assertion is plausible. Furthermore, I believe Grès’s approach to design may have been the catalyst that inspired Halston to abandon his long-time hat-making techniques. Unlike another great milliner-turned-dressmaker, Charles James, who crafted rigid and inflexible gowns, Halston instantly and completely abandoned all vestiges of his millinery vocabulary and opted to design only soft, fluid, easily wearable clothing.

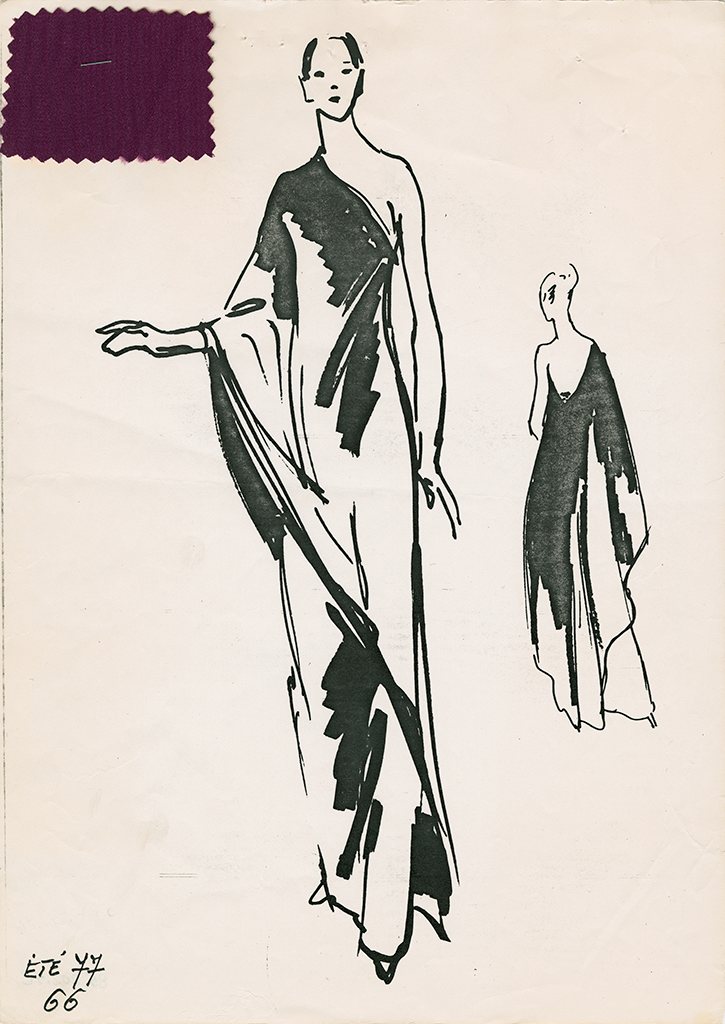

During the 1960s and 1970s, Grès was a revered figure as well as a formidable force in fashion. By amplifying her swirling method of draping honed during the early phase of her career in the 1930s, Grès’s “op-art dresses and flowery gowns for ‘couture hippies’,” as Vogue described them in 1966, led to a resurgence of editorial coverage of her work by leading fashion magazines. Having ready access to haute couture while working as the house milliner for Bergdorf Goodman during the 1960s, Halston must have known that Grès was a master technician and one of greatest dressmaking innovators of the twentieth century. Halston, like Grès, crafted garments from geometrically shaped pattern pieces and bias draping.

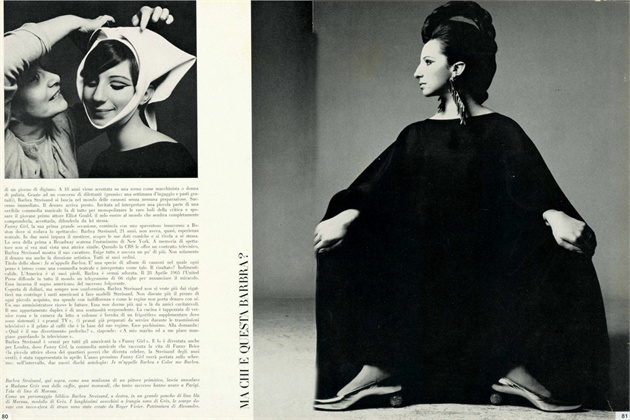

Barbara Streisand wearing Madame Grès in Vogue Italia, May 1966. via Vogue Italia.

However, while there is evidently a shared aesthetics, upon close examination, their respective designs are revealed to be distinctly dissimilar. Halston’s caftans and gowns could never be called copies or stylistic appropriations of Grès’s.

Grès tended to cut and fold her creations with less complexity than Halston did his. For example, her coral-colored wool jersey ensemble (in the MFIT permanent collection) is comprised of a simple, tubular skirt on the bottom, and, on top, a hip-length tunic that dips dramatically in the back. Made from one piece of material and cut on the straight grain, the shape of the tunic’s pattern resembles a rectangle on three sides; the fourth, longer side is deeply curved (with two lobes and one deep dip) like one side of a violin. The drama of the garment comes not only from the simplicity of the pattern but also from Grès’s bias-draping.

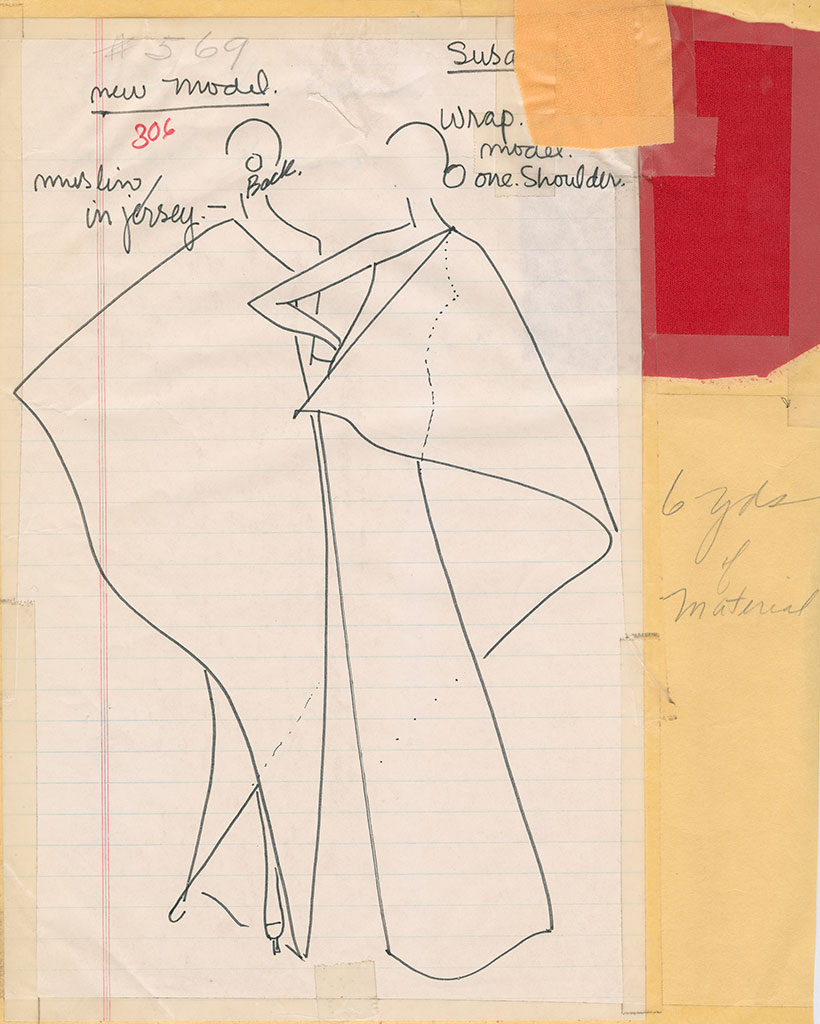

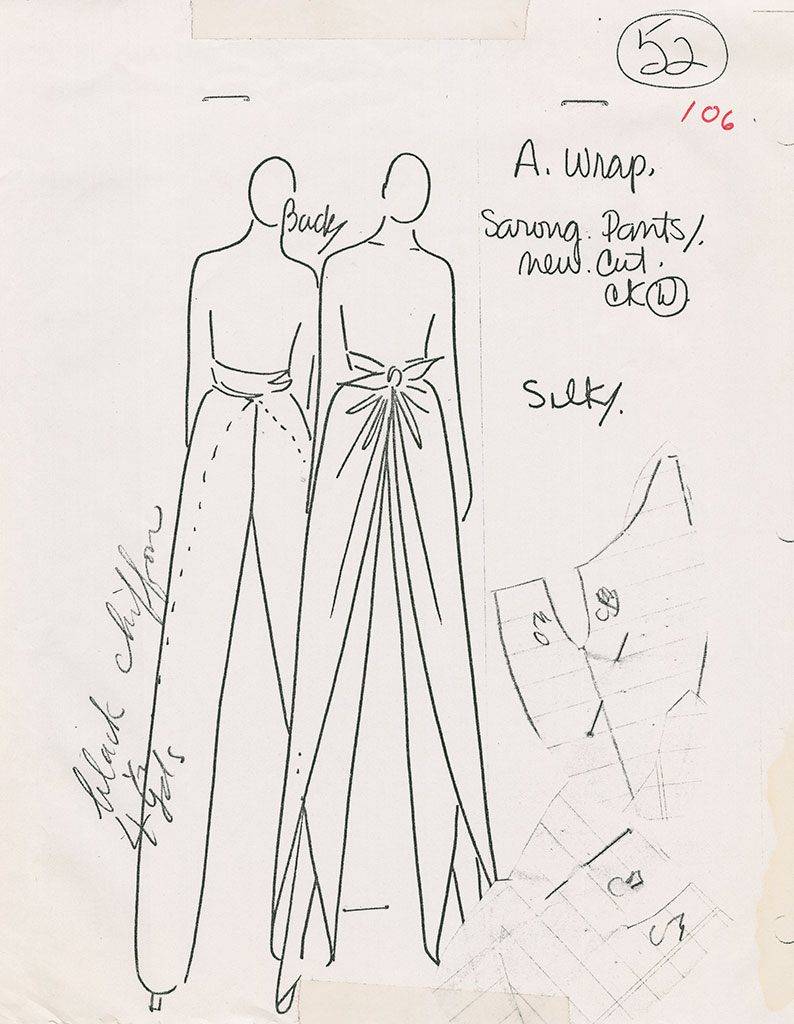

Halston crafted his loose and billowy caftans a la Grès by draping on the bias, using lengths of fabric cut on both the straight grain and the bias, but he took the construction one step further by folding and assembling his versions in more complex patterns. For example, his red synthetic caftan, embroidered with long, parallel rows of red bugle beads, is a brilliant version of his “envelope,” a construction process that was also used to make loose pajama tops and caftans. One pattern piece, shaped like a parallelogram, is folded on the bias and draped over the head and shoulders, then folded again on the sides, along the straight grain, around the body.

One of the most sophisticated of Halston’s creations is his celebrated, spiral cut, “tube” dress dating to around 1976. Referred to as the “sarong” dress, this strapless, floor-length garment gained its moniker because of a knotted closure positioned above the bust. Its construction, however, was a complete departure from the loose, wrapped Polynesian skirt for which it was named. Much more a couture creation, the sarong-tie dress obtained its body-skimming silhouette from a single length of deftly draped, bias-cut, silk. A length of fabric was first cut into the shape of a parallelogram, then meticulously folded and sewn along the bias to form a swirling spiral. The seam of the dress—if viewed diagrammatically when wrapped and sewn together—resembles the red stripes of a candy cane.

In terms of innovation, the phase of Halston’s creative career from the mid-1970s to the end of the decade was his greatest. His work did more than echo the groundbreaking technical approach to construction practiced by the greatest of couturières, such as Madame Grès. It clearly reflected Halston’s unique and modern approach to design and the creation of a style for which he could undoubtedly claim authorship.

Love this post? Share it on social media with the links below. Stay tuned for more curatorial insights, and tweet using #YSLhalston.

–MM

Yves Saint Laurent’s Rive Gauche Revolution

Yves Saint Laurent’s Rive Gauche Revolution