1960s Fashion Photography

- By The Museum at FIT

- In Expedition Research Fashion History Objects Publication

- Tagged with Allan Ballard Antonia Bioeckesteyn Arctic Circle Bob Richardson Carolyn Cowan China Machado Cornwallis Island Diana Vreeland fashion Harper’s Bazaar James Terence Brady Jill Kennington John Cowan Mary Kruming Michelangelo Antonioni Mongolian lamb Patricia Mears photography Resolute Bay Richard Avedon Russian snow leopard Space Age The Museum at FIT Vogue

- On 11 Oct | '2017

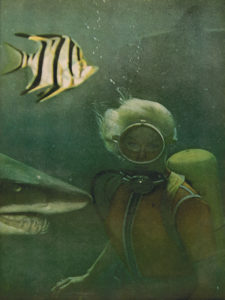

Harper’s Bazaar, May 1966, photograph by Bob Richardson / Art Partner.

One of the most compelling components of Expedition: Fashion from the Extreme was fashion photography of the 1960s. My fellow curators, Liz Way and Ariele Elia, and I all found this decade to be the era in which expeditions made a decided impact on high fashion. Not only were designers turning to the Space Age, deep sea diving, and the Arctic for inspiration, so too were fashion editors. We were so taken with the vibrant imagery that we chose John Cowan’s girl on an ice floe as the “poster girl” for our exhibition and book.

The influence of expeditions on 1960s fashion photography was celebrated brilliantly in the pages of leading magazines throughout the decade. This phenomenon is understandable, as the rise of youth styles and the deterioration of established fashion codes allowed photographers to experiment far beyond their studios. Magazine editors occasionally styled models in actual space suits and diving equipment. They also clad their models in outrageous fashions while diving in the ocean or standing on the frozen tundra.

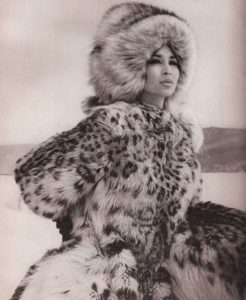

China Machado, Russian Snow Leopard by James Terence Brady of Bonwit Teller, St. Donat, Quebec, June 25, 1962, photograph by Richard Avedon. © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

Despite the less-than-enlightened approach of some fashion imagery, dramatic location shoots became a mainstay of Vogue magazine from 1963 to 1971, when Diana Vreeland was its editor-in-chief. Dynamic and highly creative, Vreeland consistently pushed the limits of fashion styling and photography throughout her decades-long career. She was among the first editors to oversee location shoots around the world while an editor at Harper’s Bazaar during World War II. By the time she arrived at Vogue, Vreeland not only expanded the scope of travel to exotic locations, she amped up the glamour quotient and sense of daring.

Vogue, November 1964, photograph by John Cowan. Copyright The John Cowan Archive.

Among Vreeland’s most interesting ideas was an editorial shoot that appeared in the November 1964 issue, shortly after her Vogue appointment. She chose British photographer John Cowan to capture her fantasy of high fashion among the icebergs. Cowan was an inspired choice: he was celebrated for a dynamic style that reflected the energetic atmosphere of 1960s Swinging London. Cowan, together with his partner, model and photographer Jill Kennington, “sparked an exciting period of high-octane image-making for numerous magazines.”³ An inspiration for the main character in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up, Cowan’s “energy and unconventional approach” inspired one of the film’s most memorable scenes. According to Kennington, the “David Hemmings–and-Veruschka scene for Blow-Up was pure Cowan. Antonioni must have seen him working — I never saw anyone else take pictures quite that way. The shooting on the floor downwards, completely fluid, unhindered by tripods, etc., was typical Cowan.”⁴

Fashion historian and journalist, vogue.com staffer Laird Borelli-Persson⁵ wrote that the fashion team comprised Cowan, Kennington, fellow model Antonia Bioeckesteyn, photography assistant, Allan Ballard, and sittings editor Mary Kruming. That group, accompanied by the Canadian Royal Mounted Police, or Mounties, found their way north to Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island in the Arctic Circle. According to Borelli, they had more than the cold to contend with: there were the unnerving silence, blinding brightness, and technical difficulties. “The day started,” according to Cowan, “when Mary Kruming said, ‘John, the sun’s shining.’ The first problem we had was that both the Hasselblad cameras froze. We presume they froze as the shutters wouldn’t work. Then we found that the film was bending and cracking because of the cold. Roughly, apart from one time when we really had a blast of fabulous sunshine (we had waited five or six days for it), we worked normal working hours, governed by the canteen food.”⁶

Vogue, November 1964, photograph by John Cowan. Copyright The John Cowan Archive.

We are most grateful to Carolyn Cowan, John’s daughter, for generously allowing us to use these beautiful images in all components of our exhibition and on the cover of our book. Thank you indeed, Carolyn.

Expedition: Fashion from the Extreme runs through January 6, 2018 at The Museum at FIT in NYC.

¹ Harper’s Bazaar, October 1962, pp. 139-147.

² Ibid, 139.

³ Victoria and Albert Museum, London, online collection database, retrieved September 24, 2016

⁴ Jill Kennington quoted by Philippe Garner, “Photos: Antonioni’s Blow-Up and Swinging 1960s London,” Vanity Fair, April 2011, online interview.

⁵ Laird Borrelli-Persson, “How to Look Chic in the Antarctic, the Vogue Way,” Vogue.com, 14 February, 2016.

⁶ Mary Kruming, as quoted by Borrelli-Persson.

⁷ Vogue, November 1964.

⁸ Ibid.

Q & A with MFIT's Senior Exhibition Manager

Q & A with MFIT's Senior Exhibition Manager