Network of Nature

Naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) revolutionized society’s view of the natural world. Considered the father of ecology, Humboldt understood the vast diversity of nature to be an interconnected global force. He also believed that emotions and artistic expression were integral to a true experience and understanding of nature. The objects displayed here illustrate this diversity and the creativity it inspires.

-

Image InfoClose

Network of Nature Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Water is the essence of all life on earth. Simulating water striking a hard surface, this one-of-a-kind, translucent dress “splashes” away from the body. To create it, Iris Van Herpen used hot air guns and metal pliers to mold sheets of acrylic. “I look to nature a lot and also to the processes within nature . . . technology is inspired by natural processes,” Van Herpen explained.

Iris van Herpen Splash dress (Left)

Acrylic glass, 2013, Netherlands, Created in collaboration with SHOWstudio and Daphne Guinness, 2017.6.1, Museum purchase.Iris van Herpen with Jólan van der Wiel Magnetic Motion Shoes (Right)

Polyurethane, metal, and leather, 2014, Netherlands, 2017.6.2, Museum purchase. -

Image InfoClose

Alexander McQueen Dress and corset (Left)

Silk and leather, 2009, England, Natural Dis-Tinction, Un-Natural Selection collection, 2014.38.1, Museum purchase.The 19th-century botanical imagery on this dress represents the natural world “untouched” by man. McQueen paired the dress with an embossed corset in his spring/summer 2009 collection, which was inspired by Darwin, the Industrial Revolution, and human recklessness towards nature. McQueen used angular silhouettes and dark colors in other parts of the collection to express his anxieties over mankind’s destruction of the planet.

Alexander McQueen Dress (Right)

Digitally printed silk satin and chiffon, 2010, England, Plato’s Atlantis collection, 2010.77.1, Museum purchase.Plato’s Atlantis, McQueen’s final and most acclaimed collection, imagined the devolution of man and a return to the seas where life began. Nature again emerged as McQueen’s principal theme, expressed in groundbreaking, digitally-engineered patterns inspired by terrestrial as well as aquatic life. The dress seen here features an imaginative blend of python and crocodile patterns.

-

Image InfoClose

Arzu Kaprol Evening Ensemble

The graphic print on this ensemble, a dark sky illuminated by charges of electricity, captures the transient beauty of lightning and the explosive power of nature. A sculptural jacket and floor length gown envelop the wearer, projecting an aura of strength.

Printed synthetic stretch knit and nylon, Fall 2014, Turkey, 2015.31.2, Gift of Arzu Kaprol.

-

Image InfoClose

Rick Owens Ensemble

Rick Owens contemplated the extinction of the prehistoric mastodon in his fall 2016 collection, in which he provided bleak commentary on potential environmental devastation. Shapes and colors of the mighty mastodon are suggested by the gray, crushed velvet cape and a furry, undulating angora mini dress — which is meant to give the illusion of evaporating.

Cotton, linen, velvet, mohair, and leather, 2016, France, Mastodon collection, 2016.92.1, Gift of Rick Owens Studio.

The Botanic Garden

During the Enlightenment, exploration of exotic lands introduced Europeans to unfamiliar forms of plant life. Naturalists began identifying plant species from around the world, reinforcing the public’s fascination with natural science. Botanic gardens showcased the new and exotic plants. They became places where all social classes could reconnect with nature, and they served as sources of artistic inspiration. By the 19th century, botanic gardens had also become reputable laboratories for scientific investigation.

-

Image InfoClose

The Botanic Garden Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Robe à la francaise, 1760-1775, American (textile French, 1760s),

Bouquets of carnations and peonies fill the expansive body of this dress, while a fly-fringe trim suggests delicate flower buds. Robes à la française were renowned for the beauty of their floral textiles, perhaps encouraging literary metaphors of women as cultivated flowers. While botany was a male-dominated scientific discipline, women were encouraged to study flowers and tend to gardens.

Silk brocade, 2017.2.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Jacket and waistcoat (Left)

Wool and linen with silk embroidery, circa 1790, USA, P80.5.7, Museum purchase.In his poem The Loves of Plants (1789), Erasmus Darwin dramatized botanist Carl Linnaeus’s ideas about the sexuality of flowers. Set in a botanical garden, the poem anthropomorphizes sexual reproduction in plants, promoting a view of nature as romantic and seductive. The floral embroidery on this jacket and waistcoat captures that same provocative spirit.

Robe à l’anglaise (Right)

Silk damask, circa 1775, England, Fabric by Anna Maria Garthwaite, 1751, 2008.4.1, Museum purchase.This robe à l’anglaise is made from a textile with a woven pattern of fruit and flowers designed by Anna Maria Garthwaite. One of Spitalfield’s most famous designers, her passion for the natural history of plants rivaled that of her male counterparts in the natural sciences.

-

Image InfoClose

Romanticism emphasized the roles of imagination and emotion in the relationship between humans and nature. The floral motif of this dress reinforces the metaphor of women as flowers, which was recurrent in 19th-century literature. Women were often seen as nurturing caretakers of the garden.

Dress, printed cotton, 1830-1833, USA, 94.92.1, Gift of Ms. Marcia Wallace.

-

Image InfoClose

This wedding gown is trimmed with sprays of faux orange blossoms and vibrant leaves of grass that appear to sprout from the dress. As a symbol of virginity, eternal love, and marriage, orange blossoms commonly adorned 19th-century wedding gowns. Brides who were said to be “sunk in the greenery” resembled walking flower gardens, emphasizing woman’s connection to nature.

Wedding dress, silk, circa 1875, USA, 83.85.2, Gift of Mrs. Cora Ginsburg.

The Science of Attraction

Few principles of scientific thought have had more impact on society than Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution. Published in 1859, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species became a widely popular text despite, or perhaps because of, its controversial subject. In his later work The Descent of Man (1872), Darwin elaborated on a concept he had introduced earlier: sexual selection. Examining ideas about beauty and attraction across species, Darwin concluded that animals and humans had the same “taste for the beautiful.”

-

Image InfoClose

The Science of Attraction Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Evening dress (Left)

Silk, velvet, taffeta, and net, circa 1859, USA, P91.23.3, Museum purchase.Along with silk tassels, tiers of cut and un-cut velvet form the ornamentation of this dress. In The Descent of Man, Charles Darwin observed that in humans, females were the more “ornamented” of the sexes and the more aesthetically evolved. This reading of sexual differentiation contributed to the Victorian preoccupation with sex roles.

Man’s suit (Right)

Wool, circa 1860, USA, P90.2.4, Museum purchase.George Darwin, a son of Charles Darwin, published the essay “Development in Dress” in 1872. He argued that natural selection was also operative in dress. “[I]n animals and dress, remnants of former stages of development . . . preserve a tattered record of the history of their evolution,” he wrote. Focusing on menswear, he argued that features of men’s coats, such as buttons or tails, are analogous to vestigial parts of an organism.

-

Image InfoClose

Yves Saint Laurent (Rive Gauche) Man’s suit

Bold colors make for “conspicuous” sexual displays. According to theories of sexual selection, such flamboyant signals advertise a male’s suitability to potential mates. This form-fitting, bright green velveteen suit by Yves Saint Laurent has similar connotations, reinforcing the association between showy displays and desirability.

Velveteen, circa 1972, France, 88.170.1, Gift of John Karl.

-

Image InfoClose

Halston Ensemble

Bold fields of red and black create a striking effect on this ensemble. The color red elicits powerful responses in every known culture, and its strong influence may be rooted in biology. In nature, male birds such as the scarlet tanager have evolved bright red coloration for sexual communication, an example of a phenomenon known as sensory exploitation.

Wool, circa 1965, USA, 82.42.4, Gift of Mildred S. Hilson.

-

Image InfoClose

Mme. Pauline Hat

Adorned with a bird-of-paradise, this woman’s hat is an example of how feathers used by male birds in sexual display have been appropriated by fashion to emphasize female allure. Birds-of-paradise, which include some of nature’s most flamboyant avian species, were described by naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace as “the most beautiful of the feathered inhabitants of this earth.” Today, birds-of-paradise are protected against the harvesting of feathers.

Felt and taxidermic bird-of-paradise, circa 1955, USA, 77.146.2, Gift of Mrs. Otto Grun.

-

Image InfoClose

Mr. Fish Jacket

The vibrant psychedelic pattern on this jacket captures the flashy style of the late 1960s Peacock Revolution, which brought a colorful and flamboyant look back to menswear. This trend aligned with processes in the natural world, where it is most often the male of a species who is the more visually arresting.

Wool blend, metallic thread, circa 1970, England, gift of Wendy Sacks and Joseph Holdner, 2008.15.1.

The Language of Flowers

During the 19th century, many publications explored “the language of flowers.” These popular books promoted the notion that the species and colors of flowers held symbolic meaning — prompting, among other things, the exchange of coded bouquets. Yet flowers project a conspicuous duality. On the one hand, they suggest innocence, beauty, and refinement; on the other, as the reproductive organs of plants, they represent sexuality.

In 1735, botanist Carl Linneaus established that plants reproduce sexually, and he promoted a romantic analogy, comparing plant sexuality to human love-making. As one journalist wrote, flowers are “the literal and figurative representation of layered femininity.” Their complex meanings often find expression in fashion.

-

Image InfoClose

The Language of Flowers Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Charles James evening ensemble

With its petal-like stole, this evening gown transforms the wearer into a flower, giving her a sensual elegance. Couturier Charles James often envisioned his clients as exotic flowers and believed that fashion should arouse the mating instinct. Psychologist Nancy Etcoff writes, “Flowers are alluring landing strips for pollenating insects: They are the plant world’s sex objects.

The Tree evening dress, silk taffeta and netting, 1955, USA, 91.241.127, Gift of Robert Wells in memory of Lisa Kirk.

The Petal evening Stole, silk satin and velvet, 1955, USA, P87.31.11B, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Alexander McQueen Evening dress

Otherworldly images of orchids by photographer Peter Arnold creep across this columnar dress. According to Alexander McQueen, orchids were “pivotal” to his Pantheon ad Lucem collection. Despite the fragile beauty of orchids, they survive under difficult conditions and often grow as harmless attachments on trees. It is likely that these qualities of strength, beauty, and survival appealed to McQueen.

Printed silk, 2004, England, Pantheon ad Lucem collection, 2016.104.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Pierre Hardy Shoes

This pair of shoes challenges customary representations of flowers. Pierre Hardy rendered realistic images of lilies in saccharine, artificial colors that he described as “acidic in the style of Warhol or Gilbert & George.” This was the first time Hardy had depicted flowers in a spring collection, and he said, “I tried to deal with them a different way.”

Leather, 2015, France, 2016.18.1, Gift of Pierre Hardy.

-

Image InfoClose

Chanel (Karl Lagerfeld) Evening dress

This little black dress by Karl Lagerfeld references the camellia, an emblem of the House of Chanel. Many couturiers have had signature flowers. It is believed that Coco Chanel preferred the camellia to other flowers partly because one is worn by the courtesan heroine of Dumas’s Le Dame aux Camélias, symbolizing purity of heart.

Silk and synthetic net and plastic, circa 1989, France, 2014.63.3, Gift of Anonymous.

-

Image InfoClose

Isoude (Katie Brierley) Eirene evening dress

The color of this dress was produced by using a natural dye derived from the root of Common madder (rubia tinctorum), a flowering perennial that produces a yellow flower. It has been used as a dye for more than 5,000 years, yielding a spectrum of colors that includes pink, coral, reds, russet, and brown.

Tussah silk, organza, mother of pearl, 2010, USA, gift of Katie Brierley, Isoude, 2010.18.1.

Investigating Nature

Victorian culture fostered an understanding of nature based on intensive investigation, with everything from ocean life to microorganisms under examination. The knowledge acquired through empirical research, aided by refinements in technology, was used to catalogue and organize the natural world.

The microscope revealed hidden worlds to naturalists such as Ernst Haeckel. Also an artist, Haeckel illustrated his discoveries in his seminal book, Art Forms in Nature (1899-1909). By introducing these forms and structures to the general public, Haeckel significantly influenced design disciplines, including fashion, and helped to bridge the gap between art and science for future generations.

-

Image InfoClose

Investigating Nature Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Mrs. M.A. O’Connell Dress

Ferns were the subject of an intense “mania” during the Victorian era. One of the oldest forms of plant life, the fern metaphorically captured the majesty of primordial time. Collecting ferns became one of the few hobbies to transcend class and gender barriers. Fern motifs, such as the one on this dress, appeared on everything from clothing to tombstones.

Silk, brocade, and beads, circa 1888, USA, P87.20.42, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Jeanne Lanvin Evening dress (Left)

Cotton organdy and net, circa 1930, France, P82.28.1, Museum purchase.The scalloped layers of this dress overlap to create a pattern reminiscent of large fish scales. Couturier Jeanne Lanvin was often influenced by eastern cultures, where ornamental fish, such as the Asian arowana, are highly valued.

Christian Dior Dress (Right)

Cotton, spring 1954, France, 92.70.5, Gift from the Elizabeth Parke Firestone Collection.Christian Dior’s appreciation for nature’s harmony is evident in his design patterns. This dress depicts a kaleidoscope of symmetric shapes that resemble marine organisms. The beauty of many natural forms derives from their symmetry, an essential “language” of pattern and form in nature.

-

Image InfoClose

Oscar de la Renta Suit (Left)

Linen, silk, and glass, 1992, USA, 94.16.1, Gift of Oscar de la Renta.The appliqué on this jacket by Oscar de la Renta suggests an elaborate coral reef. Coral reefs are unique ecosystems; a major one is located in the Caribbean, where Oscar de la Renta grew up. The designer’s fondness for coral is evidenced by the name of his Dominican Republic estate: “Corales.”

ThreeASFOUR Dress (Right)

Cotton, silk, and synthetic net, 2016, USA, 2017.16.1, Museum purchase.Geometry is at the heart of designs by ThreeASFOUR. For its spring 2016 collection, this fashion design collective explored fractal patterns rendered as elaborate textile prints, such as the one on this dress. “It’s something that’s everywhere and unites all of us. There is a certain proportion that nature follows. This is sacred geometry,” explains Adi Gil, one of the trio of artists who are ThreeASFOUR.

The Aviary

“Birds dwell at the heart of human experience,” writes naturalist Mark Cocker. Laden with symbolism, they feature prominently in the art, literature, and folklore of many cultures, past and present. Birds have come to represent transformation, freedom, honor, grace, and a myriad of other exalted principles and virtues.

Feathers are the defining features of birds, affording them an alluring sense of mystery and unsurpassed beauty. Their expressive and kinetic qualities have captured the human imagination for millennia. Not surprisingly, fashion designers have exploited these qualities to create garments that celebrate their splendor.

-

Image InfoClose

The Aviary Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Bill Cunningham Cape and comb set (Left)

Pheasant feathers and plastic, 1960s, USA, 2013.79.1, Gift of Frederick Eberstadt.Feathers exhibit an astonishing diversity of color, pattern, and form. They allow birds to fly, keep warm, and convey sexual intention. Feathers are also commonly associated with notions of freedom. This matching cape and headpiece project a liberated sexuality in keeping with the zeitgeist of the 1960s fashion.

Cristóbal Balenciaga Evening dress (Right)

Silk chiffon and ostrich feathers, 1967, France, 87.19.1, Gift of Ms. Roxanne Lowit.This evening gown accentuates the delicate lightness of feathers, a biological material often employed by the haute couture. The gown’s ethereal quality was achieved by using ostrich plumes to abstract the silhouette. Feathers often symbolize mobility and emancipation, and by the 1960s, Balenciaga’s minimalist style had encouraged a liberation of the body.

-

Image InfoClose

Gabrielle Chanel Evening cape

The subdued use of feathers on this cape demonstrates Chanel’s modernist approach to design. Elaborate displays of plumage had adorned women’s hats at the turn of the century, but here, feathers project reserved luxury, in keeping with the simplicity of Chanel’s design.

Silk crêpe de chine and feathers, 1927, France, 96.69.15, Gift from the Dorothea Stephens Wiman Collection.

-

Image InfoClose

Alexander McQueen Dress

The elaborate feather pattern of this dress envelops the wearer in the primary component of avian beauty. In turn, the sculptural bustle and train suggest the tail of an exotic bird. “I am inspired by a feather’s shape, but also its color, its graphics, its weightlessness, and its engineering,” McQueen said. “I try to transpose the beauty of a bird to women.”

Silk, 2009, England, Horn of Plenty collection, 2016.63.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Paul Poiret Evening coat

Paul Poiret’s designs often made exotic references. The collar and cuffs of this coat are trimmed with fringe that evoke a vulturine bird of prey. Referencing these formidable birds projects an aura of strength and authority, a reminder that Poiret’s clothes were not for the timid woman.

Silk faille and gold thread, 1908, France, 91.255.11, Gift from the estate of Tina Chow.

-

Image InfoClose

Comme des Garçons Evening ensemble (Left)

Silk, rayon, tulle, cotton, nylon, and velvet, 2007, Japan, Rising Sun collection, 2015.55.5B-D and 2010.57.5, Jacket: Gift of Daphne Guinness, Suit, top, belt: Museum purchase.Comme des Garçon’s spring 2007 collection was designed around the red disc of the Japanese flag, symbolic of the rising sun. A red disc is also a feature of the red-crowned crane (Grus japonicas), a bird traditionally highly regarded in Japan. Kawakubo’s predominantly red, white and black collection included tee-shirts emblazoned with phrases such as “simplicity, nature, beauty.”

Alexander McQueen Dress (Right)

Printed silk, 2009, England, Horn of Plenty collection, 2016.14.1, Museum purchase.Birds are symbolic of transformation in the arts and religions of many cultures. The birds on this dress morph into a houndstooth pattern. They were inspired by the illustrations of M.C. Escher as well as by Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds (1963). Alexander McQueen’s fascination with birds began during his childhood. He once told a journalist that he envied birds because they were free.

Metamorphosis

In 1830s Chile, a German naturalist named Renous was arrested on charges of heresy after it was discovered that his caterpillars had turned into butterflies. This kind of transformation, exhibited by insects and their relatives, is metamorphosis, not heresy. It is the most radical form of physiological change in the natural world — and one of nature’s most awe-inspiring processes.

With its similarly profound ability to transform appearance, fashion has often generated analogies to metamorphosis, while designers have established literal and figurative associations between their garments and natural imagery. Their designs aim to transform the body and with it, notions of beauty.

-

Image InfoClose

Metamorphosis Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Dolce & Gabbana Evening dress

Dolce & Gabbana prominently featured butterflies in their spring 1998 collection. According to the New York Times, the handmade appliqués symbolized life and rebirth. Butterflies have appeared in fashion for centuries, often called upon for their beauty, but also to represent the phenomenon of metamorphosis, the most radical form of change in nature.

Silk chiffon and crêpe, 1998, Italy, 98.45.1, Gift of Robert Dolce & Gabbana.

-

Image InfoClose

Charles James La Sirene evening dress

Charles James designed several versions of this dress style, popularly referred to as his “Lobster dress.” The tucks on this example radiate outward from a central, spine-like form, suggesting the overlapping plates of the crustacean’s exoskeleton. Lobsters, in fact, undergo a process of metamorphosis and represent a Surrealist trope common to the paintings of Salvador Dalí.

Silk crepe, 1940, USA, 71.265.13, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Detail of Charles James Swan evening dress

Silk chiffon, satin, netting, and boning, 1954-1955, USA, 91.241.136, Gift of Robert Wells in memory of Lisa Kirk.

-

Image InfoClose

Charles James Swan evening dress

By abstracting the body, this gown suggests the silhouette of a swan with wings folded across its back. Charles James produced dresses that capture the essences of living things, such as bird or butterflies, by accentuating the body plan, or bauplan, of the organism. Introduced in the 1940s, the term bauplan refers to morphological features that together define an organism.

Silk chiffon, satin, netting, and boning, 1954-1955, USA, 91.241.136, Gift of Robert Wells in memory of Lisa Kirk.

-

Image InfoClose

Thierry Mugler Evening dress

Glamour and fantasy are hallmarks of Thierry Mugler’s designs. His spring 1989 collection drew inspiration from the legendary city of Atlantis. The segmented body of this dress suggests a transformation from unsightly crustacean to sensual siren. Mugler has been called a “master of metamorphosis,” who dresses the body in “exoskeletons derived from the animal kingdom.”

Polyester and Lurex, 1989, France, Les Atlantes collection, 2011.13.1, Museum purchase.

Into the Wild

The patterns on animal skins have evolved in ways that increase an animal’s chances for survival in the wild. Some forms of “camouflage” mimic an animal’s natural surroundings so that it “disappears” into its environment. Others distort the contours of the body so that the animal cannot be easily singled out or detected.

Designers are attracted to the bold visual impact of animal patterns. In fashion, however, patterns are used to make the wearer stand out rather than blend in. The aesthetic appeal of animal patterns also derives from their folkloric, exotic, and even sexual connotations.

-

Image InfoClose

Into the Wild Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Rudi Gernreich Ensembles

These animal-pattern outfits by Rudi Gernreich explore the notion of clothes as a second skin. As part of the designer’s “total look” concept, customers could also purchase matching underwear, hoods, shoes, and gloves, thus affecting a complete transformation. These ensembles blurred the lines between human and animal.

(Left) Polyester tricot, 1966, USA, 82.153.72, Gift of Mitch Rein.

(Right) Nylon knit, 1966, USA, 82.153.149, Gift of Mitch Rein. -

Image InfoClose

Patrick Kelly Dress

The zebra stripes on this dress morph into a fingerprint, perhaps alluding to the uniqueness of a zebra’s stripes. Just as no two people have the same fingerprint, no two zebras have the same stripe pattern.

Printed cotton, 1988, USA, 2016.82.14, Gift of Bjorn G. Amelan and Bill T. Jones.

-

Image InfoClose

Manolo Blahnik Shoes

The graphic patterns presented in certain animal skins have been appropriated by fashion designers for both their visual impact and their implicit sensuality. The erotic appeal of Manolo Blahnik’s peep-toe stilettos is heightened by their exotic zebra print, beckoning a walk on the wild side.

Zebra-printed pony skin, 1998, England, 98.77.1, Gift of Manolo Blahnik.

Physical Forces

Physics is the study of matter and energy, from “the largest galaxies to the smallest sub-atomic particles.” It has led to advances in astronomy, electromagnetism, geophysics, meteorology, and many other scientific fields. Physics has provided some of human history’s most profound — and abstract — ideas about the natural world and how it works.

Maria Mitchell, the first female astronomer in the United States, said that science is “not all mathematics, nor all logic, but it is somewhat beauty and poetry.” Discoveries about the universe fascinate humankind. They take hold in our culture, where they are celebrated, revered, and even feared. And they find expression not only in textbooks, but in our art and, of course, our clothing and textiles.

-

Image InfoClose

Physical Forces Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Pierre Cardin Dress

During the Cold War, the physical sciences became an arena of competition that contributed to escalating global tensions. Yet Space Age fashions became a symbol of youth and modernity, projecting an idealized future made possible through science. The vinyl appliqué on this Pierre Cardin dress suggests atomic particles.

Synthetic, spring 1969, France, 80.261.9, Gift of Mrs. Walter Eytan.

-

Image InfoClose

Yvonne May Evening coat

The dazzling, descending comets on this evening coat project a sense of motion and speed. During the early 20th century, these astral phenomena were extensively studied by scientists and artists alike. In 1915, for instance, Albert Einstein‘s general theory of relativity proposed that massive objects cause distortions in space and time that are experienced as gravity.

Velvet, circa 1920, France, 81.88.1, Gift of John J. Sasek.

-

Image InfoClose

Saks Fifth Avenue Cocktail dress

The rhinestones and spangles on this dress imitate a shimmering galaxy of stars. During the 1950s, the allure of space travel captured the imaginations of many nations, while technological advancements facilitated new and better ways to examine the universe. In spite of Cold War tensions, a belief that science could shape the world for the better prevailed.

Silk faille, rhinestones, and spangles, Fall 1953, USA, 75.69.3, Gift of Sophie Gimbel.

-

Image InfoClose

Mary Katrantzou Ensemble

Mary Katrantzou’s spring 2015 collection referenced plate tectonics and the constant reorganization of land masses. In this enesmble, beaded “plates” mounted on a sheer bodice are surrounded by a sea of fluid silk, suggesting a world in flux. Plate tectonics are powered by gravity, one of the four fundamental forces of physics.

Silk, chiffon, and beads, 2015, London, 2017.25.1, Museum purchase.

Fashioning A Future

Fashion has long exploited the natural world as a source of raw materials, and its impact on the environment has been largely detrimental. Today, however, designers and their companies are beginning to engage in sustainable practices, with some assuming a proactive role by supporting initiatives intended to reverse the damage. In 2014, the luxury company Kering enacted a twenty-year-plan to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and sustainably source all of its materials.

The applied sciences are in turn revolutionizing technology’s relationship with nature. In fashion, there is a growing interest in biomimicry — technologies that imitate elements and processes of the natural world. These new directions are facilitating a renewed connection to nature, one that repositions humans as part of an interconnected whole.

-

Image InfoClose

Fashioning A Future Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Berthe Tally Hat

The practice of sacrificing birds for sartorial adornment was most evident in women’s hats such as this one featuring a pair of wings. Considered elegant by the dictates of fashion, many decried the “dead-bird wearing gender” as cruel. Conservation societies, such as The Audubon Society, offered public lectures to educate the public and erected Audubon-approved millenary displays.

Straw and feathers, circa 1901, France, P84.14.3, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Giorgio di Sant’Angelo Ensemble

Published in 1962, Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring exposed the negative effects of pesticide use, precipitating the modern environmental movement in the United States. By the end of the decade, hippie fashions were promoting a “back to nature” aesthetic. For this ensemble, designer Giorgio di Sant’Angelo incorporated natural materials, such as shells and feathers into its design.

Cotton, suede, shells, feathers, buttons, and stones, 1968, USA, 88.1.153, Gift of Marina Schiano.

-

Image InfoClose

Jean Paul Gaultier Top and skirt

During the 1980s and 1990s, the fashion industry came under sharp criticism for its use of fur. Reacting in part to pressure from organizations like PETA, designers began creating faux fur garments, such as this Jean Paul Gaultier top. However, this alternative to real fur has been associated with harmful chemical effects on the environment.

Top: Cotton/synthetic, taffeta, and lycra, 1988, France, 1988, France, P88.76.2, Museum purchase.

Skirt: Lycra and polyamide, 1987, France, P87.47.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Valentino Couture Set

The cheetah has often been used as a status symbol to signify wealth and luxury. Its power and grace has inspired designers like Valentino, who created this couture coat. But demands for exotic furs encourage poaching and endanger many species. Since the 1970s, animal organizations have worked to demystify the allure of wearing fur. “It is really the one area where money and ethics converge in fashion,” one luxury consultant remarked.

Wool and cheetah fur, 1974, Italy, 96.84.1, Gift of Mary Russell.

-

Image InfoClose

Stella McCartney Dress (Left)

Printed viscose, Resort 2017, USA, 2017.13.1, Gift of Stella McCartney.This dress from Stella McCartney’s 2017 resort collection is made of sustainably sourced viscose from Sweden. Viscose is a rayon fiber typically derived from wood pulp. Production of it has contributed to extensive deforestation of wildlife habitats. McCartney promotes awareness of product origins and has been a leader in developing eco-friendly practices. She foresees a day when the environmental costs of production will be indicated on garment labels.

J. Crew T-shirt (Right)

Printed linen, 2017, USA, 2017.4.1, Gift of Stella McCartney.Bees pollinate over one-third of the plants we consume, and many species are threatened by habitat loss. This year, a species of bumblebee became the first to be added to the endangered species list. This T-shirt was designed by J. Crew to raise awareness about diminishing bee populations. Fifty percent of the retail cost was used to support The Xerces Society, an invertebrate conservation organization.

-

Image InfoClose

Speedo Fastskin II Swimsuit (Left)

Polyester, lycra, and titanium silicon, 2011, USA, 2011.12.1, Museum purchase.Created by Speedo, the Fastskin FSII swimsuit mimics the physical properties of sharkskin to reduce drag and increase speed in water. Tiny ridges on the bodice of this biomimetic design replicate the function of dermal denticals found on the surface of a shark’s skin, while its tight fit compresses muscles to act like a second skin.

The Lost Explorer Black Magic suit (Left)

Japanese slub cotton and Schoeller Ecorepel®, 2017, USA, 2017.21.1, Gift of David de Rothschild.Featuring Ecorepel waterproofing technology, this Black Magic cotton suit by The Lost Explorer imitates the ways in which water naturally rolls off of leaves and duck feathers. The Lost Explorer was founded by committed environmentalist David de Rothschild out of his desire “to elevate and celebrate [nature’s] status as a magician through our designs.”

-

Image InfoClose

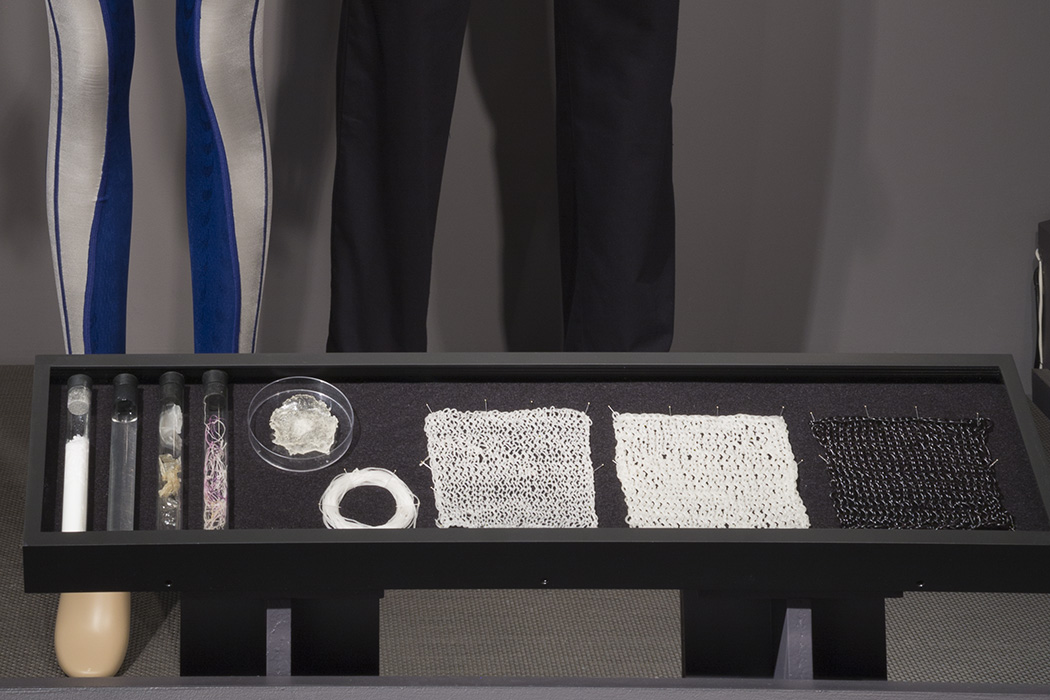

AlgiKnit Process materials and knit samples

Alginate is a polysaccharide found in the cell walls of brown algae. The alginate displayed here has been fashioned into paste, sheet, and filament. Once extruded to form a filament, it can be knitted like a traditional yarn. The resulting textile is biodegradable, and can serve as nutrient for future iterations, creating a production cycle that is a fully closed loop. AlgiKnit grew out of “BioEsters,” a team of FIT students who won the 2016 National BioDesign Challenge.

Alginate BioYarn, 2017, USA, AlgiKnit’s research is being supported by Dr. Brown and Dr. Oliva.