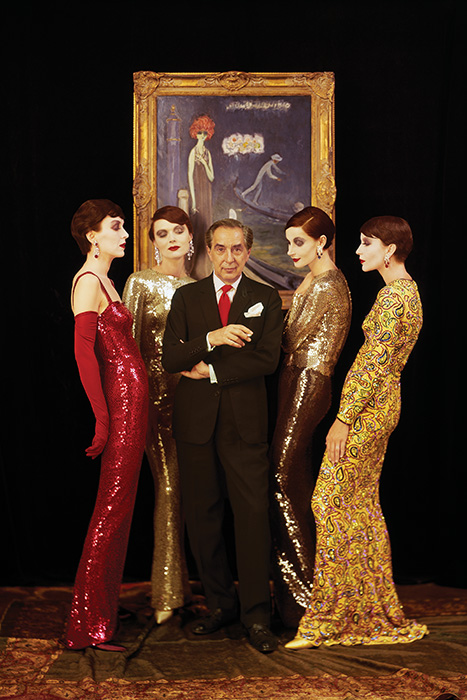

Norman Norell

Born Norman David Levinson in Noblesville, Indiana, the designer adopted the more soigné moniker of Norman Norell soon after studying illustration and fashion design in New York during the early 1920s. He moved seamlessly from student to costume designer and by 1924 had begun his career as a fashion designer. At the onset of World War II, Norell entered into a two-decade business partnership with garment manufacturer Anthony Traina and produced award-winning collections under the Traina-Norell label. In 1960, Norell bought out his investors and his name alone began to appear on the label.

-

Image InfoClose

Norman Norell

Norell was revered in the fashion industry and lauded during his lifetime. He won numerous prestigious industry awards, including Neiman Marcus in 1942; Parsons medal for distinguished achievement in 1956; Sunday Times of London International Fashion award in 1963; City of New York Bronze Medallion in 1972; and an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the Pratt Institute in 1962. In 1965, Norell was elected the second president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. He also won the first Coty American Fashion Critics in 1943, and four more in 1951, 1956, 1958, and 1966.

Photograph by Milton H Greene ©2017 Joshua Greene, archiveimages

Norell Signatures

Although Norell was not the first American designer to employ couture techniques, he was the most important creator to codify them at the ready-to-wear level. He was also one of the primary creators to profoundly alter existing perceptions about New York’s Seventh Avenue garment industry, at the time derisively called the “rag trade.” So outstanding was the quality of his ready-made dresses, coats, and suits that critics deemed his designs “the equal of Paris,” earning him another title — “The American Balenciaga.”

-

-

-

-

Image InfoClose

Belt

Pink wool evening coat with matching skirt and blouse, 1964. The Museum at FIT. Gift of Lauren Bacall.

-

Image InfoClose

Capes

Norell was a master when it came to crafting coats with dramatic “Puritan” collars. Both the collar suits and the capes on view in this section are beautifully shaped. In the Norell ateliers, woolens would be blocked (shaped with heat and steam) then stabilized with only one layer of interfacing, specifically a stiff but nearly weightless linen called wigan. Light and flexible, these shapely coats and suits were also resilient and still look remarkably fresh more than half a century after they were made.

Belted dresses with mini capes in pink linen and black wool, 1964. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Cape

Traina-Norell, candy pink silk faille cape, 1958. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Cape

Ice blue wool gown and jacket with Pilgrim collar, fall 1968. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Cape

Norell was a brilliant colorist who imbued his daytime clothes with a sense of drama. Suits, dresses, and coats were made in a range of colors, from inky dark shades such as black and navy to warm neutrals like beige and camel, as well as an assortment of jewel tones, clear pastels, punchy “Crayola” colors, and even saturated acidic hues. Norell could deftly mix contrasting or complementary colors with ease. He also punctuated solid colored garments with large, plain, contrasting buttons. On occasion, Norell opted for stripes, dots, and checks.

Double-breasted wool melton cape, 1962. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Cape

Blue Pilgrim collar wool coat, fall 1968. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Belt

Belts were a common Norell design element. He made them in every width — from pencil-thin to the span of a hand — and would place them under the bust, atop the hip, or anywhere else along the torso. All of Norell’s belts were made by leading craftsman Ben King. Built of leather, suede, or matching self-fabric, each belt was as carefully constructed as Norell’s clothes. Often made with rows of channel stitching, these belts cinched dresses and suits with a flattering, finished look.

Bubblegum pink wool jersey dress with belt, 1966. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Bow

One of Norell’s signature design elements was his “pussycat” bow. Prominently positioned at the front of the throat, this bow was a long and confident extension of the blouses worn beneath his elegantly cut suits. Norell also incorporated the bow in evening tops that he paired with long skirts or beaded trousers. Even though the organza-lined “pussycat” was a vibrant feminine flourish, it never overwhelmed

the wearer.Black wool suit with silk bowed blouse, 1968. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Bow

Navy wool dress with silk scarf and leather belt, 1967. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Bow

Heathered oatmeal wool jersey shirtwaist dress with silk scarf and belt, 1971. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

The Sailor Suit

Norell grew up wearing sailor suits, so is it perhaps not surprising that this look was one of his favorites. He produced countless versions throughout his career. His nautical style dresses ranged from those with gigantic balloon sleeves and skirts crafted out of organza to slim, sleeveless shifts made from linen. No matter the shape, each one had the requisite bow and square, back-draped collar. Norell’s sailor bows were big, bold and made with stiff silk organza to keep them shipshape.

-

-

Image InfoClose

Drawing

After working as a costume designer in theater and film during the early 1920s, Norell seamlessly transitioned into clothing design as a designer for a wholesale manufacturer. But his career took a quantum leap in 1928 when he went to work for Hattie Carnegie, owner of one of the leading fashion houses in New York and an elite purveyor of licensed copies of Parisian haute couture. Norell learned much during his twelve-year tenure under the formidable Carnegie. The mitered, candy-striped dress seen here is a rare surviving example of Norell’s early work.

Norman Norell for Hattie Carnegie, striped evening ensemble, 1932. Drawing by Michael Vollbracht. © Michael Vollbracht.

-

Image InfoClose

Sailor Dress

Wool jersey sailor dress, 1972, Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Sailor Dress

Linen blue sleeveless sailor dress, 1963, Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Sailor Dress

Cotton organdy sailor dress, spring 1968. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Sailor Dress

Cotton organdy evening gown with red bolero jacket and peacock sash, 1968, Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

Menswear Inspired

Norell’s family owned and operated a successful haberdashery, where he was exposed to menswear fabrics, cuts, and details from an early age. Like a number of leading designers, Norell began in the early 1940s to infuse women’s clothes with the practicality and aesthetics of menswear. Among the best examples of this masculine/feminine fusion are his coats. He used heavy woolens and large-scale plaids to craft double breasted-silhouettes, while regularly appropriating details such as back belts, functional buttonholes, and ample pockets.

-

-

-

-

Image InfoClose

Double-Breasted

Wool pink and ivory plaid double breasted coat, 1965. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Double-Breasted

Yellow double breasted jacket and black dress, 1964-1966. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Double-Breasted

Charcoal wool flannel suit, 1965. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Pants for Women

Along with the culotted day suit Norell pioneered in 1960, the introduction of his pantsuit preceded versions made by Parisian couturiers by a couple of years. And like his culottes, which inspired couturiers and were pirated by the American ready-to-wear industry, Norell’s prescient pantsuit would change the fashion landscape. However, few could match the perfect proportions and exalted workmanship of the Norell original.

Wool herringbone coat and pants ensemble, 1970. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Blocked Tailoring

Prince of Wales tweed reefer coat, late 1960s. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

The 1920s

Norell’s favorite period in fashion history was the 1920s, the decade he began his design career. Ever the modernist, Norell readily embraced the emancipated woman who began to shorten her hair and her hemlines while discarding her corsets. He also collected paintings by Fauve artist Kees van Dongen, whose subjects with kohl-rimmed eyes, bobbed hair styles, and tubular moderne silhouettes greatly influenced Norell’s later designs and his cabine of house models.

-

-

-

-

Image InfoClose

Beige wool crepe double breasted jacket with sleeveless gown. 1963-1966. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Black and copper animal print tank dress, 1965. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Ivory and black wool suit, 1965. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Pink silk crepe trapeze dress with silver bugle beads, 1966. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Pale yellow silk crepe ensemble, 1966. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Butter yellow wool tunic and skirt ensemble, 1965. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Black and gold wool crepe and sequin chemise dress, 1966. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

Materials

Norell used only the finest and most luxurious materials. Among them was fur. However, Norell did not craft coats or any other type of garment made entirely of fur. Instead, he chose to trim his day and evening wear with mink, fox, and sable. The judicious use of this expensive and sensuous material elevated the glamour quotient of his restrained daywear.

-

-

-

Image InfoClose

Fur Trim

(LEFT) Oatmeal wool fur-trimmmed suit, 1967.

(RIGHT) Red and black checked fur-trimmed suit, 1962.

Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Satin and Chiffon

Black and white striped satin ball skirt with fur trim, 1967. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Beads

Silver and crystal beaded empire-waist gown, 1964. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Beads

Pale pink beaded culottes dress, 1961. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Wool

Red wool crepe evening dress, 1962. The Museum at FIT. Gift of Claudia Halley. Photograph by Eileen Costa © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

Wool

Nutmeg wool tweed dress, circa 1965. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Wool

Black wool crepe evening dress, 1967. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Wool

Black wool crepe dress with jeweled buttons, 1965. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Wool

Black wool jersey bodice and skirt, 1963. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Beads

Black beaded dolan-sleeve gown, 1968, Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

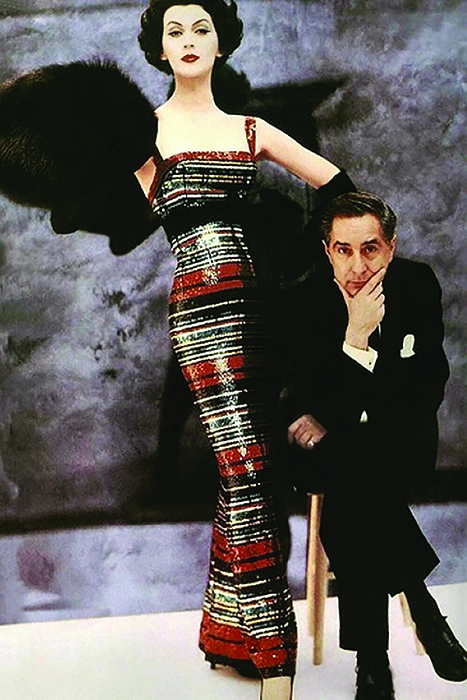

Mermaids

Aptly called the “mermaid,” Norell’s shimmering, sequin-covered evening gown is arguably his most recognizable creation. Like many designers, he was influenced by Hollywood costumes, especially those created during the Golden Age. In fact, Norell began his career working for both Brooks Costume Company and Paramount Pictures during the 1920s. It is not surprising that he was one of the most successful at incorporating silver screen glamour in his luxurious ready-to-wear evening garments, especially his “mermaids” gowns.

-

-

Image InfoClose

What made Norell’s mermaids so successful was his ability to strike the perfect balance of physical comfort and visual impact. Most often, he made the gowns using a base of knitted silk jersey. The base was then covered with a dazzling pavé of hand-applied sequins that were dyed repeatedly to match the jersey. Each of the tiny, reflective discs was sewn on with its own unique stitch pattern, allowing the sequins to shift and move independently. The result was a garment that reflected the maximum amount of light.

Purple sequined “mermaid dress, 1965. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.

-

Image InfoClose

Traina-Norell, roman-striped, sequined evening sheath worn by Dovima, 1959. Photograph by William Helburn.

-

Image InfoClose

Traina-Norell, gold evening coat and dress in cashmere, silk jersey and sequins, circa 1958. The Museum at FIT, Gift of Lauren Bacall. Photograph by Eileen Costa © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

Purple “mermaid” dress, silk jersey, sequins, circa 1965. The Museum at FIT, Gift of Mortimer Solomon. Photograph by Eileen Costa © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

While most of Norell’s sequined “mermaid” evening dresses were slim and sleek, he made them in a wide array of colors and with varying necklines and arm coverings, from high turtlenecks with long sleeves to body-baring halter necks. Norell was like an artist whose meditation on a single theme produced a myriad of variations. The assemblage on view is but a sampling of his prolific output.

Off-white and blue silk jersey and sequin “mermaid” dress, circa 1972, The Museum at FIT, Museum purchase. © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

Gray “mermaid” dress, silk jersey, sequins, 1968-1969. The Museum at FIT, Gift of Lauren Bacall. Photograph by Eileen Costa © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

Camel hair and paillette theater suit, 1971. Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler.