Introduction

The ideal fashionable body has shifted throughout history to emphasize different shapes and proportions. It is a perpetually changing cultural construct, yet does not feel so fluid in daily life. It can loom over us as a rigid expectation, affecting how we view and treat our bodies, as well as how we view the bodies of others.

The fashion industry has historically approached the body — particularly the female body — as malleable, something that can be molded and changed with the cut of a garment, sculpting underwear, diet, exercise, and even plastic surgery. The Body: Fashion and Physique explores this complex history to reveal the variety of body shapes that, over the past 250 years, have been considered fashionable.

-

Image InfoClose

Introduction Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

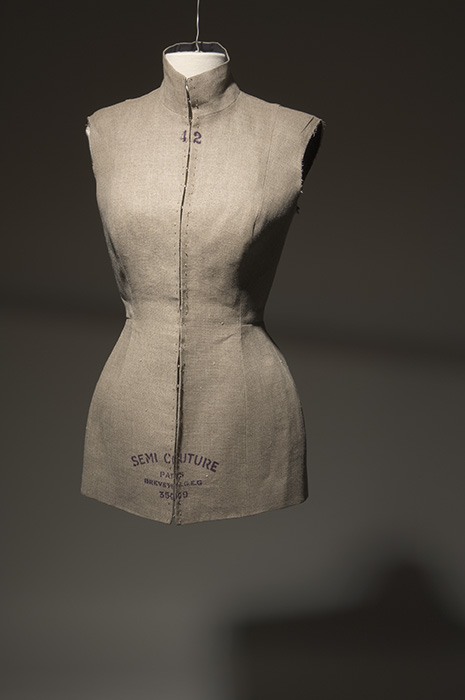

Martin Margiela Tunic

This tunic by Martin Margiela mimics the look of dress forms, which are used to fit garments while they are being designed. The specific shape of dress forms has changed over time, in tandem with the fashionable silhouette. By transforming the wearer into a dress form, Margiela highlighted the artificial nature of the idealized fashion physique.

Beige linen, spring 1997, France, 2008.91.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

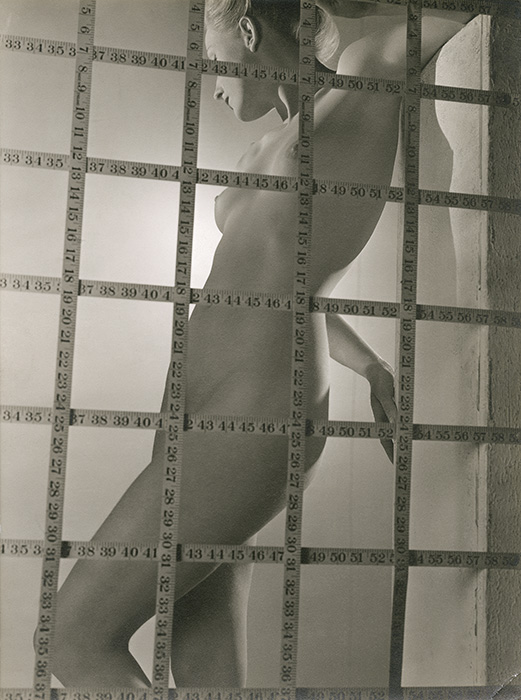

John Rawlings Photograph

Photographer John Rawlings produced this image for Vogue to accompany an article titled “Get a Sense of Proportion.” The nude model is literally imprisoned behind a cage of measuring tapes, perhaps alluding to the enslaving pressures of fashionable body ideals.

1939, USA, 71.269.17, gift of The Estate of John Rawlings.

18th and 19th Centuries

Before the twentieth century, the ideal female figure was a mature, curvaceous body, punctuated by a narrow waist. To emphasize the narrowness of their waists, women wore boned undergarments called corsets, or stays. During the eighteenth century, stays were largely reserved for women and girls of the elite. Technological innovations during the nineteenth century made corsets available to a much wider demographic of women. By the end of the century, women of all classes were expected to wear them, including pregnant women. Skirt silhouettes also changed a number of times during the nineteenth century to emphasize particular proportions.

-

Image InfoClose

18th and 19th Centuries Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Dress

This dress is designed to be worn with a crinoline — a hooped structure underneath the skirt that widens its circumference. The extreme diameter is meant to make the wearer’s waist appear narrow by comparison.

Off-white silk taffeta, satin, and tulle, circa 1865, Scotland, 75.227.41, gift of Mildred R. Mottahedeh.

-

Image InfoClose

Dress

The particular proportions of bustle dresses varied throughout the 1870s and 1880s. Some bustles protruded sharply from the lower back, giving the silhouette a hard, angular look. Others used swags of fabric draped at the back or hips to lend a softer appearance.

Purple silk crushed velvet, circa 1887, England, 2014.38.3, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

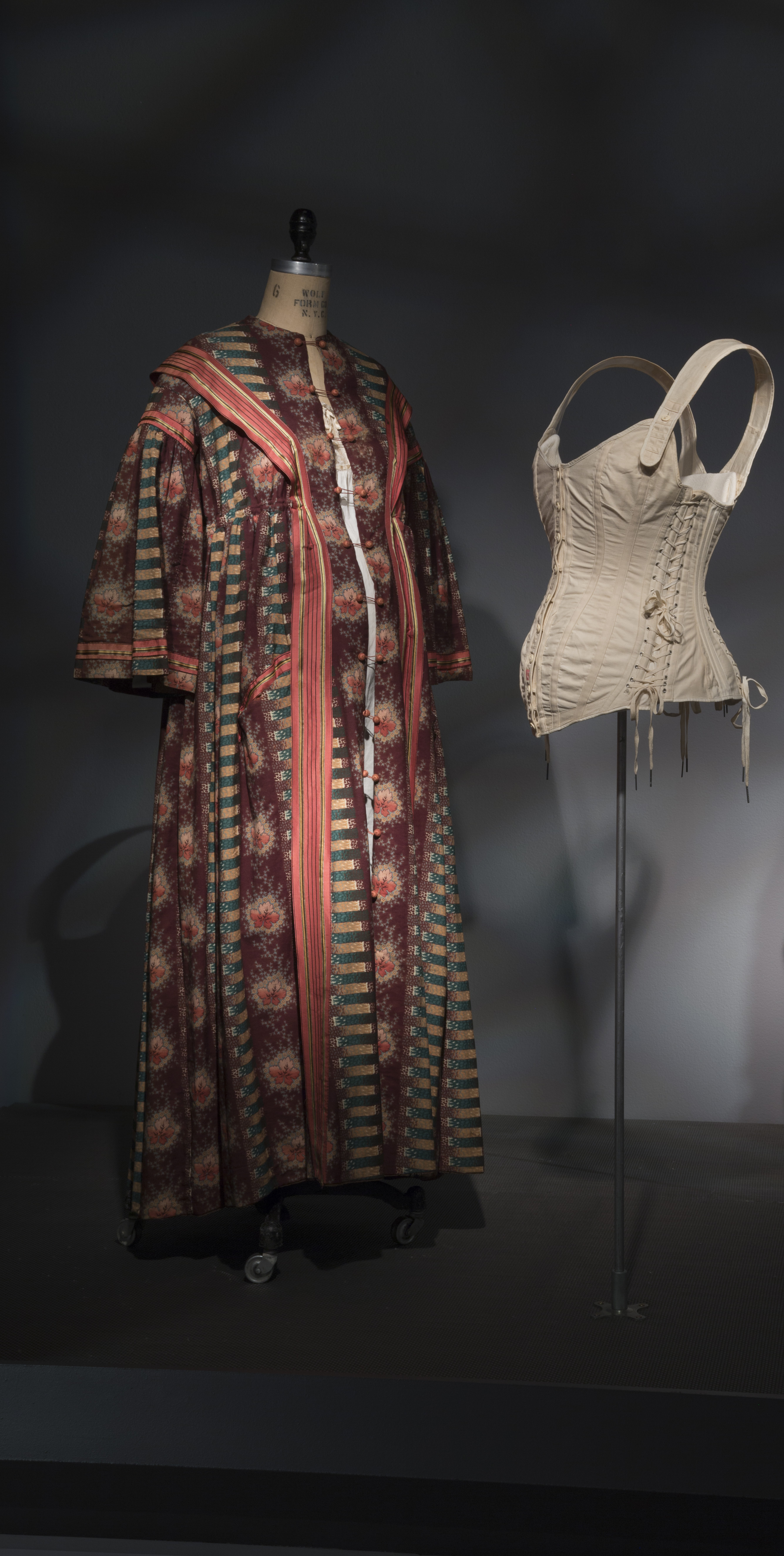

The maternity robe on the left was created for a pregnant woman to wear during her “confinement”— a 19th-century custom that dictated expectant mothers should remain inside their homes when they could no longer conceal their pregnant bellies, which were considered inappropriate for public display. Maternity corsets were intended to help women camouflage their changing bodies, but they were also considered necessary to give support to the wearer’s back and belly.

Maternity Robe (Left)

Printed wool, 1860s, USA, 70.15.16, gift of Mrs. Margaret Riggs.Ferris Bros. Maternity Corset (Right)

Off-white cotton, circa 1900, USA, P82.31.2, Museum purchase. -

Image InfoClose

Joseph Johnson Dress

This evening dress has a waist circumference of approximately 18 inches (with a 31-inch bust; the wearer’s hip measurement is difficult to estimate due to an excess of fabric). We have no way of knowing whether or not the wearer reduced her normal waist by tightly lacing her corset. However, the practice of “tight-lacing” was probably not as common nor as extreme as we assume. According to Valerie Steele, “the idea that most women in the past had ‘wasp waists’ needs to be radically revised.”

Dusty pink silk satin and lace, circa 1895, England, 2007.27.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

There is a common misconception that all 19th-century women had 18-inch waists. This stereotype has been perpetuated in literature and film, most notably in Gone With the Wind, when Scarlett O’Hara laments that she can no longer fit into her 18.5-inch corset. Yet advertisements of the time promoted corsets from 18 to 30 inches, and ready-made corsets were avaialble in further sizes — the pink corset here has a 32-inch waist. Women could also adjust the way their laces were tied and how tightly they closed their corsets, in some cases leaving an inch or more open at the back.

Corset (Left)

Black cotton sateen, pink lace, 1880, France, 98.29.4, Museum purchase.Horner Corset (Right)

Pink cotton sateen, circa 1880, USA, P91.43.2, Museum purchase.

1900-1910s

At the start of the twentieth century, the female body ideal began to shift from a soft, curvaceous figure to a thinner, younger physique — what Dr. Valerie Steele has described as the change “from an opulent Venus to a slender, athletic Diana.” Women were increasingly encouraged to exercise and engage in sports. Garments grew looser and shorter, and boned corsets were replaced with stretchy foundation garments known as girdles.

-

Image InfoClose

1900-1910s Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Dress

The silhouette of this dress (with its raised waistline and tiered skirt) was pioneered by designer Paul Poiret. Poiret experimented repeatedly with uncorseted styles during the first two decades of the 20th century. While his designs were generally looser around the waist, they narrowed at the hips, promoting a slender physique.

Silk chiffon, satin, lace, fur, and velvet, circa 1913, USA, 2014.48.3,

Museum purchase. -

Image InfoClose

Liberty of London Dress

This Liberty of London dress was designed to be worn without a corset. The English department store opened in 1875, specializing in “artistic” or “aesthetic” dress, which drew inspiration from medieval fashion in order to create alternatives to corseted looks. Aesthetic styles garnered support from dress reform activists, but were widely viewed as eccentric, at-home garments.

Silk velvet, circa 1910, England, P90.83.2,

Museum purchase.

1920s-1930s

The dominant silhouette of the 1920s was short and loose for both day and evening wear. Dresses were cut away from the body to highlight a straight and lean figure, but as fashion scholar Lauren Downing Peters observes, the tubular style effectively “eliminated the body underneath the dress.” The more “generous” nature of the loose-fitting silhouette allowed a ready-to-wear plus-size industry to flourish for the first time. Then referred to as “stout wear,” it was pioneered by retailer Lane Bryant.

-

Image InfoClose

1920s-1930s Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

House of Paquin Gown and Slip

The tubular silhouette of the 1920s gave way during the 1930s to a much more fitted style, cut to skim the wearer’s curves. The girdle grew in popularity because it compressed the wearer’s hips and waist in a way that allowed movement and flexibility, even as it slimmed the region and prevented “unsightly” jiggling.

Metallic silk, lame, silk satin, circa 1935, France, 2013.37.1, Gift of Marilyn Ludtke.

-

Image InfoClose

Dress (Left)

Sequins and beads on net, circa 1926, USA, 90.190.5, gift of Elinor Toberoff.Ensemble (Right)

Peach silk crepe, peach chiffont, circa 1928, USA, P83.22.3, Museum purchase.

1940s-1950s

Strong, padded shoulders dominated during the early 1940s and were replaced by narrow shouldered, full-skirted ensembles by the 1950s. However, the fashionable physique remained slender, as evidenced in fashion magazines, which continually recommended wearing foundation garments and keeping a regimen of light diet and exercise to attain (and maintain) the ideal fashion shape.

-

Image InfoClose

1940s-1950s Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Los Angeles-based designer Gilbert Adrian used prominent shoulder pads in both his casual daywear and his more formal designs. This silhouette dominated during the 1940s and was considered “masculine” in its proportions — not only for the broad shoulders, but also its narrow hips. Adrian popularized the style in his fashion collections as well as in his costume designs for MGM studios.

Adrian Suit (Left)

Wool, circa 1945, USA, 78.239.5, gift of Joe Simms.Adrian Dress (Right)

Black silk, circa 1945, USA, 71.206.2, gift of Maybell Machris. -

Image InfoClose

Detail of Adrian Dress

Black silk, circa 1945, USA, 71.206.2, gift of Maybell Machris.

-

Image InfoClose

Christian Dior Dress and Petticoat

This evening dress by Christian Dior shows the key elements of the designer’s famed “New Look”: a nipped-in waist and long, full skirt. Dior first unveiled the silhouette in 1947. By the early 1950s, it had become the dominant fashion. The style exaggerated the slenderness of the wearer’s waist with a boned understructure and tulle petticoats.

Ivory silk satin with embroidery and rhinestones, 1951, France, 75.86.5, gift of Despina Messinesi.

1960s-1970s

During the 1960s and 1970s, the fashionable ideal became increasingly young and thin, epitomized by the model “Twiggy.” Designers began making clothes that were more body-revealing, rejecting girdles and other foundation garments. This gave rise to a dieting craze, and a new culture of physical fitness.

-

Image InfoClose

1960s-1970s Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

With the increased exposure of the body in 1970s fashion (seen in the Halston at left) shaping undergarments became difficult to conceal. Diet and exercise became the preferred ways to attain a fashionable physique. Dance and “aerobics” became the most popular ways to “work out,” and stretchy, skin-tight unitards like the one on the right became de facto uniforms.

Halston Jumpsuit (Left)

Silk jersey, circa 1976, USA, 79.66.40, gift of Ethel Scull.Danskin Unitard (Right)

Cotton/Lycra spandex, 1980-1985, USA, 85.109.9, gift of Danskin, Inc. -

Image InfoClose

Norma Kamali Ensemble

Designer Norma Kamali was fascinated by the new fitness lifestyle and drew on athletic attire in her work. The cut and fabric of the ensemble to the right takes inspiration from dancewear of the late 1970s.

Polyester jersey, circa 1977-1978, USA, 89.64.51, gift of Alan Gilliland.

-

Image InfoClose

Twiggy London Girl Dress

This mini-dress was part of a product line by British teenage model Twiggy, so nicknamed due to her skinny, twig-like frame. The short, A-line construction plays on the silhouette many designers were working with during the 1960s to “free” wearers from the heavily structured styles the previous decade. Twiggy came to embody the increasingly thin, youthful ideal of the ’60s and remains a key reference in debates about body image.

Synthetic jersey, 1966, England, 2017.20.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Rudi Gernreich Dress

This dress includes clear plastic panels down its sides, exposing the wearer’s body. Rudi Gernreich experimented with exposure of the body throughout his career. The transparent panels take the 1960s ideal of “freeing the body” to an extreme, as they likely inhibited the wearer’s ability to wear undergarments.

Black wool jersey, 1968, USA, 2002.16.1, gift of Pamela Belden Daniels.

-

Image InfoClose

During the 1970s, gay men began adopting ultra-masculine attire, a style known as the “clone” look. As Shaun Cole describes it, “The fit . . . was key; denim jeans were worn tight to emphasize the genitals . . . and T-shirts revealed the results of work at the gym.” The flight jacket further exaggerates the proportions of the upper body. Both Jean Paul Gaultier and Walter Van Beirendonck played on the idealized “hard” gym body in their work.

-

Image InfoClose

Jean Paul Gaultier Man’s Sweater

Jean Paul Gaultier created the likeness of a muscular, male torso on the surface of this sweater. It is a play on the idealized “hard” body that became fashionable during the 1980s. However, Gaultier used padding and wool to make a soft, cozy physique in which the wearer could wrap himself.

Gray wool, 1991, France, 91.256.1, gift of Richard Martin.

1980s-1990s

By the 1980s, a new fitness lifestyle had begun to develop around aerobics. The ideal became a hard, muscular body for both men and women, which designers such as Thierry Mugler and Donna Karan emphasized in different ways. At the same time, designers from Japan like Issey Miyake created oversized looks that intentionally obscured the body.

Concerns about obesity have been on the rise since the 1980s, which has likely influenced body ideals, making the extreme opposite appear more desirable. Thus the toned body gave way to a waifish ideal during the 1990s. Teenage model Kate Moss (nicknamed “the waif”) pioneered the look in provocative ads and on runways of major brands.

-

Image InfoClose

1980s-1990s Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Comme des Garçons (Rei Kawakubo) Ensemble

For this look, Rei Kawakubo distorted the wearer’s body with soft padding. It was produced for her renowned Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body collection of spring 1996. Each look included padding in various shapes and positions. The collection challenged the traditional relationship between fashion and the body, as well as the idealized female physique.

Nylon and polyurethane, spring 1996, Japan, 2015.1.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Thierry Mugler constructed the dress on the left to highlight the curves the wearer’s body. Moving away from the slinky designs of the 1970s, Mugler used heavy velvet and boning to create a structured garment. Its hard aesthetic is in line with the toned, muscular body ideals of the decade. Donna Karan drew heavily on the broad-shouldered, narrow-hipped silhouette of the 1940s when she launched her eponymous label in 1985. The bold proportions of the jacket on the right suggest a strong physique, giving the wearer the look of a body honed at the gym.

Thierry Mugler Dress (Left)

Black velvet, 1981, France, 99.80.1, Museum purchase.Donna Karan Jacket (Right)

Navy wool jersey, fall 1986, USA, 2000.32.8, gift of Carolyn Gottfried. -

Image InfoClose

The slip dress was a popular style during the 1990s. Unstructured and slinky, it shifted away from structured, 1980s designs that emphasized a toned, muscular physique. Marc Jacobs created the example on the left for a 1992 collection by the label Perry Ellis, which was inspired by “grunge” street style.

Perry Ellis (Marc Jacobs) Dress (Left)

Synthetic, fall 1992, USA, 2014.18.1, gift of Angie Lafontaine.Calvin Klein Dress (Right)

Navy blue rayon jersey, 1996, USA, 97.26.3, gift of Calvin Klein.

2000-Present

Despite attempts by some brands at greater diversity since the start of the twenty-first century, most runway models continue to be thin white girls. But the internet and social media have changed the way people engage with fashion. The industry has opened up to a growing cross section of people, and certain designers, such as Becca McCharen-Tran of Chromat, Lucy Jones, and Christian Siriano have embrace an inclusive view of the fashionable body. These designers use their brands to project the message that all bodies are beautiful and deserve to be included in fashion.

-

Image InfoClose

2000-Present Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Roberto Cavalli Dress and Corset

Italian designer Roberto Cavalli is best known for his sexy ensembles. In this evening look, Cavalli draws attention to the wearer’s posterior with a dramatic cutout. An interest in prominent buttocks emerged during the early 2000s, which some scholars have connected to the globalization of the fashion industry and the influence of different beauty ideals from around the world.

Multi-color silk crêpe de chine, 2002, Italy, 2003.45.1, gift of Roberto Cavalli.

-

Image InfoClose

Christian Siriano Dress

Christian Siriano designed this dress for actress Leslie Jones to wear to a film premiere. Jones had tweeted that due to her physique, no fashion designer was willing to dress her for red carpet events. Siriano responded, saying he would be proud to design for her. The episode sparked a public debate about the marginalization of certain body types by contemporary brands.

Red silk blend crêpe faille, 2016, USA, 2017.26.1, gift of Christian Siriano.

-

Image InfoClose

Chromat (Becca McCharen-Tran) Ensemble

This ensemble was worn by model Denise Bidot during Chromat’s spring 2015 runway show. Chromat holds some of the most diverse runway presentations in fashion, with models who range across size, race, age, and gender identity. The label is known for its architectural athletic wear and directional cage pieces that play on the construction of historical undergarments, such as the bustle and crinoline.

Black spandex and plastic boning, spring 2015, USA, 2017.53.1, Museum purchase.

-

Image InfoClose

Grace Jun designed the jacket on the left for breast cancer survivors who had undergone surgical mastectomies. Electronic components in the sleeves and sides connect to a chip hidden in the back, which records the wearer’s range of motion. The data can be accessed by a physical therapist or physician to aid in the recovery process, highlighting how technology is changing the relationship between fashion and the body.

Grace Jun Jacket (Left)

White neoprene, mesh, wire, and computer chip, 2017, USA, 2017.59.1, gift of Grace Jun.Lucy Jones creates fashionable garments for wheelchair users and people with diverse abilities who sit for extended hours at a time. Both groups are often unable to consume mainstream fashion. Jones designed the shirt to the right for a seated body. It has a cropped silhouette to prevent bunching and discomfort, and easy-to- use magnetic fasteners. The sleeves, including the example in the case, are also designed for ease of dressing.

Lucy Jones Shirt (Right)

White cotton and metal magnetic fasteners, 2017, USA, 2017.60.1, gift of Lucy Jones.