Carmel Snow

Carmel Snow (1887–1961) was born in Ireland and grew up in New York City. She began her career in journalism at Vogue in 1921. Eleven years later she “switched sides” to join Harper’s Bazaar, a move regarded as so unforgivable that more than two decades later, Vogue’s editor in chief compared Snow to Benedict Arnold.

Independent, sure of her instincts, and strong-willed, Snow regularly stood up to Bazaar’s autocratic publisher, William Randolph Hearst. In Dahl-Wolfe’s words, “she trusted her editors and artists completely, and fought commercial interests to produce a magazine of quality.” Once described as the “Queen Mother of Fashion,” Snow helped launch the careers of designer Cristóbal Balenciaga and photographer Richard Avedon. Upon her retirement, a colleague wrote, “The way that we are, that we dress, that we live in our epoch owes much to the divining taste of Carmel Snow, personnage d’exception.”

-

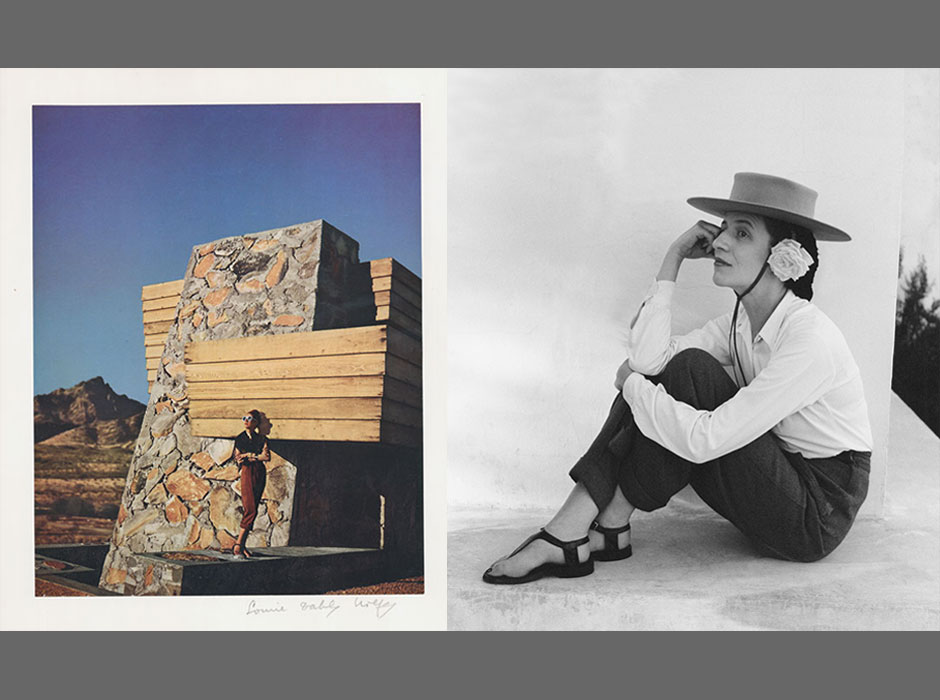

Image InfoCloseJean Patchett wearing Givenchy in Granada, Spain (Left)

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Harper’s Bazaar, June 1953, p. 71

Collection of The Museum at FIT, 74.84.269

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of RegentsCarmel Snow, Paris (Right)Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Posthumous digital reproduction from original negative, circa 1940

Louise Dahl-Wolfe Archive

©1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents -

Image InfoClose

Installation view

Mainbocher ensemble

The gray suit was a mainstay of women’s wardrobes during the post-war period and appeared frequently in Bazaar—often, as this photo suggests, as a travel outfit. Mainbocher, who began his career as a fashion illustrator for the magazine, cut the suit jacket to flare over the hips without padding. The ornamental scrollwork that anchors the collar is an example of the exquisite piecework for which his house was known.

-

Image InfoClose

Mainbocher ensemble

Wool , 1948, 77.37.14, gift of James and Mary Fosburgh

-

Image InfoClose

Mainbocher ensemble (detail)

-

Image InfoClose

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe (left)

Mary Jane Russell wearing Handmacher

Harper’s Bazaar, August 1949, p. 83

74.84.286

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Claire McCardell swimsuit

Many bathing suits of the 1940s had structured interiors that molded the body. Claire McCardell’s scandalous jersey suit, which she designed with a coordinating skirt, had neither lining nor padding. Vreeland and Dahl-Wolfe underscored the suit’s uncomplicated elegance by posing the model to emphasize her athleticism and tanned, toned limbs. The photograph, one of a series taken in Brazil, was shot at the stables of an estate near Rio de Janeiro.

-

Image InfoClose

Photograph by Louise Dahl- Wolfe (left)

Model Betty Bridges in Tijuca, Brazil wearing a Claire McCardell swimsuit

Harper’s Bazaar, May 1946

Collection of The Museum at FIT, 74.84.571

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents -

Image InfoClose

Claire McCardell swimsuit

Wool, 1946, 2002.69.1

-

Image InfoClose

Installation view

Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Louise Dahl-Wolfe (1895-1989) was born and raised in San Francisco. After attending the San Francisco Institute of Art, where she studied painting and color theory, she worked as an interior designer. When she turned her attention to photography, she applied her prior training to her new career. “I believe the camera is a medium of light, that one actually paints with light,” she said.

Dahl-Wolfe began her association with Harper’s Bazaar in 1936, when photography was becoming increasingly prevalent in American fashion magazines, replacing illustration. Dahl-Wolfe’s skill as a colorist offered a new perspective. Using a Graflex camera, or occasionally a more portable Rolleiflex, she developed an elegant, easy style of photography. Color photographs had appeared in Bazaar before, but her knack for accuracy and tone made Dahl-Wolfe’s work notable. As Carmel Snow said, “She revolutionized the Bazaar . . . because she developed color photography to its ultimate.”

-

Image InfoCloseBijou Barrington wearing eyewear from Ga-Ga-Gogs in Arizona (left)

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Harper’s Bazaar, January 1942, cover

Collection of The Museum at FIT, 74.84.60

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of RegentsSelf portrait of Louise Dahl-Wolfe (right)Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Posthumous digital reproduction from original negative

Louise Dahl-Wolfe Archive

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Diana Vreeland

Diana Vreeland (1903-1989) once quipped that because she was born in Paris, “naturally, I’ve always been mad about clothes.” She grew up in New York as a young socialite, married, and moved to London in 1929. Her time in Europe—where she mixed with the fashionable elite and befriended Coco Chanel and artists such as Christian Bérard and Cecil Beaton—amounted to a comprehensive fashion education.

In 1936, Snow hired Vreeland to write for Harper’s Bazaar. Following the success of her provocative “Why Don’t You?” column, Vreeland became the magazine’s fashion editor. Describing her job as giving the public “what they never knew they wanted,” she developed a style that was extreme and fantastical. After twenty-six years at Bazaar, Vreeland left for Vogue in 1962 and was its editor in chief for eight years. “Vreeland invented the Fashion Editor. . . No one has equaled her—not nearly,” said Richard Avedon.

-

Image InfoCloseDiana Vreeland wearing Jay Thorpe at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Rose Pauson House in Phoenix, Arizona (Left)

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Harper’s Bazaar, January 1942, p. 40

Collection of The Museum at FIT, 74.84.356

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of RegentsDiana Vreeland (Right)Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe

Posthumous digital reproduction from original negative, 1949

Louise Dahl-Wolfe Archive

©1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Claire McCardell dress

Claire McCardell was inspired by the serape, a Latin American shawl with a pattern that resembles that of the cotton she chose for this dress. Her signature brass hook-and-eye closures fasten the dress, which is shirred along the armholes to create volume, making the waist seem smaller. As the model’s pose suggests, McCardell insisted on comfort in her designs. Although Dahl-Wolfe took the photograph in the studio, it was part of a story shot on location in South America.

-

Image InfoClose

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe (left)

Model wearing Claire McCardell

Harper’s Bazaar, January 1952, p. 91

74.84.441

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents -

Image InfoClose

Claire McCardell dress

Cotton, 1952, 98.110.1, gift of Gerta Harriton

-

Image InfoClose

Installation view

Charles James evening gown

Charles James received no formal training as a designer, instead developing his idiosyncratic techniques for handling fabric from his millinery experience. James draped this evening gown’s curvaceously shaped skirt in the round. It has two zippers—one at the side of the bodice and a second that follows a curving seam along the back of the skirt. The model’s theatrical gesture emphasizes what Bazaar’s copywriter called “a dramatic dress of superbly massed cerulean satin.”

-

Image InfoClose

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe (left)

Betty Threat wearing Charles James

Harper’s Bazaar, April 1947, p. 175

Collection of The Museum at FIT, 74.84.348

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents -

Image InfoClose

Charles James evening gown

Silk, 1952, P90.63.1

-

Image InfoClose

Installation view

Christian Dior New York coat

Snow immediately grasped the importance of Christian Dior’s debut collection in February 1947. Officially called Corolle, the collection soon became known by the name Snow gave it: the “New Look.” Its influence, seen in the coat’s full skirt and narrow waist, extended into the 1950s. Dahl-Wolfe was so captivated by Dior’s designs that she ordered a suit. The model poses in front of the Château de Malmaison, former residence of the Empress Josephine.

-

Image InfoClose

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe (left)

Model wearing Christian Dior at the Château de Malmaison, Paris

Harper’s Bazaar, November 1947, p. 175

Collection of The Museum at FIT, 74.84.237

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents -

Image InfoClose

Christian Dior New York coat

Wool, 1954, 81.232.1, gift of Mrs. Despina Messinesi

-

Image InfoClose

Installation view

Carolyn Schnurer top

Vreeland covered the American market for Bazaar, which brought her into contact with designers such as Carolyn Schnurer, an early advocate of sportswear-influenced fashion. Schnurer’s resort clothes frequently incorporated culturally inspired motifs. For example, the embroidered elephants on this loose-fitting cotton top reference her trip to Ghana (then known as the Gold Coast). Vreeland styled the top, which was intended for beach wear, with what she described as “heavy Zulu necklaces and bracelets.”

-

Image InfoClose

Photograph by Louise Dahl-Wolfe (left)

Model Jean Patchett in a Carolyn Schnurer top

Harper’s Bazaar, December 1952

Collection of The Museum at FIT, 74.84.558

© 1989 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents -

Image InfoClose

Carolyn Schnurer top

Polished cotton with schiffli embroidered elephants, 1954, 82.153.78, gift of Mitch Rein

-

Image InfoClose

Carolyn Schnurer top (detail)