Fashion Capitals

Fashion today is created and shown in cities from New York to Shanghai. Yet Paris is still widely regarded as “the most glamorous and competitive of the world’s fashion capitals.” Certainly, Paris has played a very important, perhaps unique, role in the history of fashion. But Paris has also been mythologized. Paris, Capital of Fashion is the first exhibition to explore the cultural construction of Paris as the international capital of fashion. The introductory gallery places Paris within a global context, in dialogue with other fashion capitals, such as New York City.

-

Image InfoClose

Fashion Capitals Installation View

Dior’s “New Look” was central to the postwar revival of the Paris couture system. In addition to selling individual couture dresses to private clients, Dior also sold licensed copies, like this one of his “Columbine” dress, which were produced in the US for American department stores. The number of such high-end reproductions was limited,

but there were also mass-produced garments that catered to the desire for at least “a copy of a copy of a Dior.”I. Magnin and Lord & Taylor (Left) Licensed copy of Christian Dior “Columbine” dress, beige rayon and cotton satin, 1947, USA, The Museum at FIT, 91.69.4, Gift of Fay Smith

Nettie Rosenstein (Right)

New Look-inspired dress in black wool and silk faille, 1947, USA, The Museum at FIT 74.135.8, Gift of Janet Chatfield-Taylor -

Image InfoClose

Historically, Americans have been ambivalent about fashion, especially when it came from France. As one dress reformer put it: Why should “the daughters of Puritan ancestors” imitate the clothing of “the fashionable courtesan class in the wicked city of Paris?” Although some sought “to free American women from the domination of foreign fashion,” many women preferred to wear fashions originating in Paris.

Emile Pasquier (Left)

Green and brown changeant velvet and green faille ball gown with lace, beads, rhinestones, and gold metallic cord, 1889- 1890, France, The Museum at FIT, P91.55.6(Right)

Pink and green lace patterned silk robe à la française, 1750s, probably France, The Museum at FIT, 2017.46.1 -

Image InfoClose

Paris was widely regarded as the international capital of feminine fashion. But American women pioneered tailored suits, which many French women initially found too masculine. Meanwhile, London had become the capital of menswear, while New York was rapidly becoming a leader in ready-to-wear. The dress on the right bears a label identifying it as the work of “Madame Victorine,” whose shop was located at 60 West 37th Street, New York. The dressmaker might have been a French immigrant, or she might simply have adopted a French name in the belief that it sounded more stylish, thus attracting clients who could not afford to shop in Paris.

(Left)

Black wool broadcloth suit, circa 1890, USA, The Museum at FIT, 76.94.1 Gift of Cora GinsburgMme Victorine (Right)

Mauve silk faille and white wool outdoor dress, circa 1889, USA, The Museum at FIT, 98.1.1 Gift of Edith Twining -

Image InfoClose

“Battle of Versailles” Part One

The “Battle of Versailles” was a fashion show, held in 1973 to raise money for renovations at the palace. It was organized as a competition between five couturiers from Paris and five ready-to-wear designers from New York City. Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows, Oscar de la Renta, Halston, and Anne Klein were the Americans.

Yves Saint Laurent (Left)

Dark green haute couture silk taffeta gown, 1972, France, The Museum at FIT, 88.89.1, Gift of Mary RussellStephen Burrows (Right)

Rayon jersey color blocked evening dress, 1973, USA, The Museum at FIT, 2000.97.1 -

Image InfoClose

“Battle of Versailles” Part Two

Most people simply assumed that the French would “win” the competition, since Paris set the trends and dressed the world’s most stylish women, while most American designers simply copied Paris. But the Americans at Versailles ended by being wildly applauded. Not only were their clothes modern, their fashion models, ten of whom were African American, were so much more vivacious than the French models.

Stephen Burrows (Left)

Polyester chiffon color blocked two-piece evening dress, 1973-1974, USA, The Museum at FIT, 99.15.1, Gift of Mrs. Savanna ClarkHalston (Right)

White polyester and pastel iridescent sequin evening dress, circa 1972, USA, The Museum at FIT, 80.128.12, Gift of Celanese -

Image InfoClose

Jacques Fath for Joseph Halpert

Many Paris couturiers had licensing agreements with stores in New York, but Jacques Fath experimented with new types of arrangements, like his collaboration with Seventh Avenue manufacturer Joseph Halpert, who mass-produced thousands of Fath’s designs. Some foreign manufacturers found it cheaper to visit New York to buy line-for-line copies than to go to Paris.

Red silk satin dress, fall 1952, USA, The Museum at FIT, 2013.19.1

-

Image InfoClose

As early as the 1930s, there was a movement in New York to promote authentically “American” fashions. Designers such as Claire McCardell worked within the parameters of the American ready-to-wear industry to create stylish and affordable clothes. But American fashion really came into its own during World War II, when Paris was occupied by the Nazis. Lacking detailed information about the latest Paris modes, American designers looked for new sources of inspiration.

Claire McCardell (Left)

Black bias-cut rayon and silk crepe faille evening dress, circa 1939, USA, The Museum at FIT, 2005.65.9Elizabeth Hawes (Right)

Striped gray silk evening dress and bolero, circa 1932, USA, The Museum at FIT, 69.156.2 Gift of Mrs. Dudley Schoales -

Image InfoClose

During World War I, many Americans still supported Paris fashion, which they associated with French “civilization,” but during World War II, the Nazi Occupation of Paris meant that French fashion seemed “contaminated” by contact with the enemy. In the 1940s, the American press proclaimed “Paris is dead! Long live New York!” Even after Paris was liberated, many Americans were shocked by the way French couturiers lavished fabric into sleeves and skirts, something which had been prohibited in the US and the UK.

Robert Piguet (Left)

Red-orange silk shantung dress, circa 1944, France, The Museum at FIT, 70.57.61 Gift of Mr. Rodman A. HeerenJeanne Lanvin (Right)

Gray, black, and gold brocade evening coat, fall 1943, France, The Museum at FIT, 2016.114.1 -

Image InfoClose

In recent years, Asian American designers, especially those of Chinese heritage, have emerged as a significant presence in New York’s fashion world, comparable to that of Jewish immigrants in the past. To be a member of the Chinese diaspora can be advantageous when much apparel is manufactured in China and Chinese consumers are a growing force in the fashion world. In addition to his New York-based eponymous business, Alexander Wang was for a time designer at Balenciaga in Paris.

Alexander Wang (Left)

Orange and black cotton and synthetic blend mesh knit mini dress, spring 2015, USA, The Museum at FIT, 2015.17.1 Gift of Alexander WangJewish immigrants to the United States and their descendants have played an important role in the apparel industry for over 150 years. Initially focusing on the production of ready-made menswear, they later moved into retailing, womenswear, and, ultimately, the prestigious field of fashion design. In the UK and Europe, Jewish entrepreneurs and workers have also been strongly represented in the fashion industry.

Isaac Mizrahi (Right)

Cashmere and wool “Gordon” tartan plaid evening dress, fall 1990, USA, The Museum at FIT, 89.131.1, Gift of Isaac Mizrahi -

Image InfoClose

Milan is today one of the “Big Four” fashion capitals – along with London, New York, and Paris. Like France, Italy has a long and illustrious fashion history. But Italy was late to unify, and many Italian cities have competed for the title of fashion capital, among them Turin, Florence, and Rome. Milan succeeded because of its financial and manufacturing strength.

The Japanese “Fashion Revolution” of the 1980s transformed the world of fashion. Yet Tokyo ultimately failed to become a major fashion capital, in large part because the most influential Japanese designers, such as Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons and Yohji Yamamoto, decided to show their collections in Paris.

Gianni Versace (Left)

Black crepe evening dress with safety pin Medusa ornaments, spring 1994, Italy, The Museum at FIT, 2018.43.1Comme des Garçons (Right)

Black cotton tunic with white “spider web” overlay with black cotton skirt, 1984-1986, Japan, The Museum at FIT, 88.50.18, 87.56.2B -

Image InfoClose

“Ready-to-wear is in the hands of women,” declared French headlines – and, indeed, the first generation of créateurs included a number of women, such as Emmanuelle Khanh, Michèle Rosier, and knitwear designer, Sonia Rykiel.

African Americans have set many fashion trends, but, historically, they have been underrepresented as recognized fashion professionals. Like many black creatives over the years, Patrick Kelly moved to Paris in search of a more welcoming environment.

Patrick Kelly (Left)

Black wool knit dress with heart bustier design in multi-colored buttons, fall 1986, France, The Museum at FIT, 2016.48.1Sonia Rykiel (Right)

Pink and purple striped wool sweater and wool trousers, circa 1975, France, The Museum at FIT, 81.239.5 Gift of Lauren Bacall

Splendor of the Royal Court

“Fashion is to France what the gold mines of Peru are to Spain,” declared Louis XIV’s minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. The statement may be apocryphal, but already by the 1670s, fashion and luxury goods were a source of wealth and “soft power” for the French state. The splendor of the French royal court at Versailles contributed greatly to French fashion prestige — or what critics called “French fashion hegemony over Europe.”

-

Image InfoClose

Splendor of the royal court installation view

Hall of Mirrors, Palace of Versailles

Photogrammetric survey of vaulted ceiling by Art Graphique & Patrimoine© ©Art Graphique & Patrimoine. Images Art Graphique & Patrimoine©

© EPV / Thomas Garnier Château de Versailles

Installation by Leach, a subsidiary of Chargeur -

Image InfoClose

In one of his most spectacular collections for Christian Dior Haute Couture, entitled “Freud or Fetish,” John Galliano conjured up a range of dream or nightmare imagery, including this “Marie Antoinette” dress. The queen of fashion is portrayed on the left side of the skirt as a pretty faux shepherdess at Trianon, while on the right side she wears a revolutionary bonnet rouge on her way to the guillotine.

Robe à la française (Left)

Silk brocade with multicolor floral and feather bouquets and leopard pattern bows, circa 1755-1760, France, The Museum at FIT, P82.27.1John Galliano for Christian Dior (Right)

Embroidered faille dress with underskirt and metal front piece, fall/winter 2000-2001, France, Lent by Christian Dior Couture -

Image InfoClose

Robe à la française

“The French are constantly changing fashions,” declared the Dictionnaire universal (1690). “Foreigners follow the French fashion.” By the 18th century, visitors often commented on the Parisian mania for new fashions: “They invent every Day new Modes of Dressing.” In actuality, the trimmings and fabrics changed much faster than the silhouette. The robe à la française, for example, remained in fashion for a number of years.

Robe à la française, Silk brocade with multicolor floral and feather bouquets and leopard pattern bows, circa 1755-1760, France, The Museum at FIT, P82.27.1

-

Image InfoClose

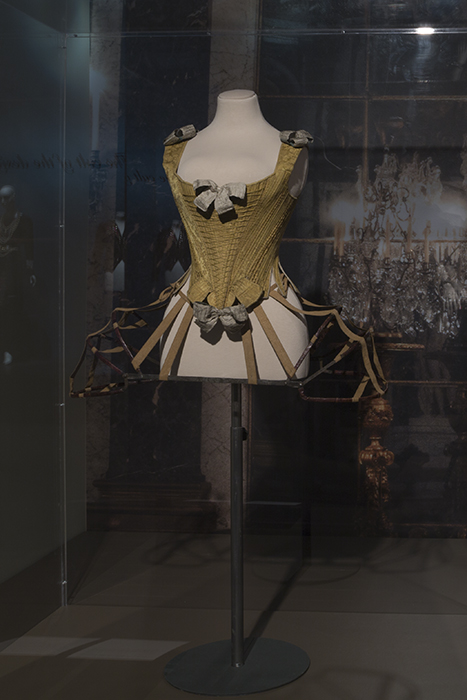

For many years, the court at Versailles and the city of Paris were so closely intertwined that they formed, in effect, a two-headed fashion capital, with Paris only gradually gaining precedence.

Silk satin damask and braided silk whalebone stays, circa 1740–60, France, Les Arts Décoratifs, collection Mode et Textile, PR 995.16.1.

Articulated pannier, leather covered Iron with fabric tape, circa 1770, France, Les Arts Décoratifs, depot du musée national du Moyen Âge-Thermes et hotel de Cluny 2005, Cluny 7875

-

Image InfoClose

Adrian

Hollywood movies helped construct a narrative of glamour around French fashion history. Adrian’s lavish costumes for Marie Antoinette (1938) provided a temporary escape from the realities of the Depression. This particular film costume was worn by Gladys George, who played Louis XV’s mistress, Madame Du Barry.

Costume for Gladys George in Marie Antoinette, 1938, USA, The Museum at FIT, 70.8.21, Gift of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc.

-

Image InfoClose

Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel

Inspired by a musical entertainment given by Louis XIV at Versailles in 1664, Karl Lagerfeld created this ravishing red and gold evening gown, “Enchanted Island.” Lagerfeld had long admired French art and culture of the ancient régime, which frequently influenced his work for Chanel haute couture.

Red haute couture “Ile enchanté” embroidered silk satin bustier dress with bracelets and embroidered shoes, fall/winter 1987-1988, France, Lent by CHANEL Patrimoine Collection, Paris

-

Image InfoClose

“Might it be possible to awaken the clothes of long-gone eras and infuse them with the spirit of today?” asked Nicolas Ghesquière. His Spring/ Summer 2018 Louis Vuitton collection juxtaposed formal French historical styles with contemporary sportswear. The embroidery on the redingote recalls the long history of refined craftsmanship in Paris.

Nicolas Ghesquière for Louis Vuitton (Left)

Cropped long-sleeve blouse, jersey shorts, and embroidered redingote, spring/summer 2018, France, Lent by Louis VuittonAlexander McQueen for Givenchy (Right)

Blue faille haute couture frock coat with silver re-embroidered lace and matching trousers, fall/winter 1999-2000, France, Lent by Texas Fashion Collection

Birth of the Haute Couture

The rise of the haute couture was crucially important to the consolidation of Paris as a modern fashion capital. In 1858, when Charles Frederick Worth established his couture house on the Rue de la Paix, Paris was already home to many “little” dressmakers, but Worth created grande (big) couture, which was soon known as haute (high) couture. Elite American women were attracted by the prestige of Paris fashion, and Worth recognized their importance as clients, saying they had “the faces, the figures, and the francs.”

-

Image InfoClose

The rise of the haute couture installation view

-

Image InfoClose

Worth & Bobergh

Charles Frederick Worth is widely regarded as the father of haute couture because he transformed the couture from a small-scale craft into big business and high art. In 1858, the English-born Worth opened his own couture house at 7 rue de la Paix, in partnership with Otto Gustave Bobergh, the son of a banker, who provided the necessary capital. The Empress Eugénie, consort of Napoleon III, was his most famous client.

Blue ribbed silk ball gown, 1866-67, France, Lent by The Museum of the City of New York. Gift of Richard H.L. Sexton and Eric H.L. Sexton, 1962.

-

Image InfoClose

Worth

In the era of high capitalism, wealthy American women flocked to the most prestigious couturiers, helping to make Paris the capital of luxury and fashion. For special private clients, even Worth would be “inspired” to create unique dresses, like Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt’s famous “Electric Light” fancy dress costume. He liked American clients, saying that they had “the faces, the figures, and the francs.”

“Electric Light” fancy dress worn by Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt, 1883, France, Lent by The Museum of the City of New York. Gift of Countess Laszlo Szechenyi, 1951.

-

Image InfoClose

Worth was the first “grand couturier.” His innovation was to move away from making a dress for an individual client (the way an ordinary “little dressmaker” did) to designing a series of models, from which his clients made a selection. Having thus asserted his authority as artist-creator, Worth turned the actual production of the garments over to his hundreds of assistants. The expression grande couture (literally big sewing) changed to haute couture, as increasing emphasis was placed on “high” artistry and luxury.

Maison du Bon Marché (Left)

Printed silk satin and blue-grey silk satin two- piece dress, 1880s, France, Lent by Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mrs. Albert Nalle, 1963Worth (Right)

Light blue satin and velvet evening dress, circa 1886, France, Lent by The Museum of the City of New York. Gift of Mrs. Ernest Iselin, 1932.

Paris = La Parisienne

The pleasures of shopping for fashion contributed to Paris’s longstanding reputation as “a woman’s city.” It was said in 1925 that “Whereas men go to London for suits and shirts, women all dream of being dressed in Paris.”

-

Image InfoClose

Paris = La Parisienne = Fashion Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

The figure of the Parisienne had long been an icon of fashionable and seductive femininity, but by the later 19th century Paris itself was increasingly perceived as a feminized and sexualized city, a dream world of pleasure, in contrast to cities like London and New York, which seemed masculine and work-oriented. In her song “That’s Paris,” Mistinguette characterizes the city as a woman, “a blonde” and “queen of the world.”

Pink and cream striped organza and satin evening dress, early 1870s, France, The Museum at FIT, 2019.1.4

-

Image InfoClose

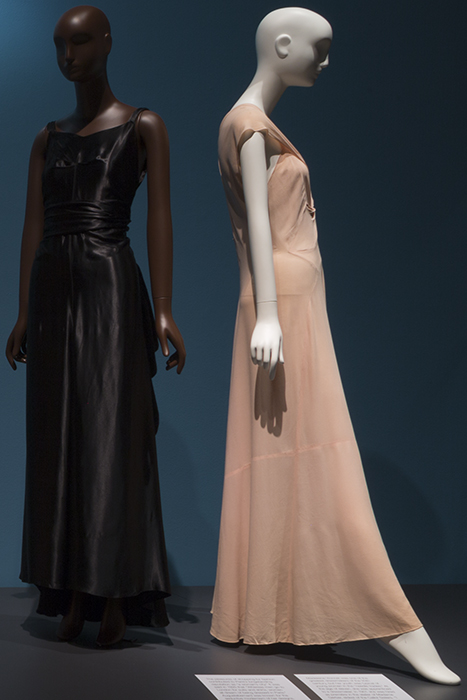

Augustabernard was known for the seductive modernism of her designs, which appealed to elegant international clients, especially South Americans. Madeleine Vionnet was one of the greatest dressmakers of the 20th century, but her youth was typical of young women in the “needle trades.” At the age of eleven, she was apprenticed to a dressmaker. In 1901 she was hired as première in the atelier of Madame Gerber, eldest of the Callot Sisters. “I have made Rolls Royces,” Vionnet later declared, “and without Madame Gerber, I probably would have made Fords.”

Augustabernard (Left)

Black satin gown, fall/winter 1931, France, Lent by Hamish BowlesVionnet (Right)

Light pink silk crepe dress, spring/summer 1932, France, Lent by Hamish Bowles -

Image InfoClose

Decades before the rise of the haute couture, Paris was already described as “the capital of fashion.” Well-known couturières, such as Madame Palmyre, plied their trade, as did milliners, corsetiers, fan-makers, and other artisans. In her Lettres Parisiennes (1844), Madame de Girardin referred to Paris as “this city of perfected elegance and marvelous luxury.”

(Left)

Printed linen day dress, circa 1837, France, The Museum at FIT, 2019.3.1(Right)

Man’s navy blue wool double-breasted tail coat, 1830-1840, USA, The Museum at FIT, 2016.1.2 -

Image InfoClose

Jean Paul Gaultier was among the créateurs who helped make French fashion so exciting in the 1980s. The way he played with conventions of sex and gender, in particular, has had a profound influence on fashion. For example, rather than using corsetry to reinforce conventional ideals of beauty, Gaultier has always emphasized that many body types, genders, and ages can be attractive.

Jean Paul Gaultier (Left)

Orange shirred velvet corset dress, fall 1984, France, The Museum at FIT, P92.8.1Jean Paul Gaultier (Right)

Man’s black wool gabardine and striped velveteen back heraldic jacket, 1988, France, The Museum at FIT, P88.76.4 Gift of Hermès -

Image InfoClose

Thierry Mugler is best known for his spectacular fantasy creations, such as his steel-corseted glamazon couture. But he also created strictly-tailored suits for both women and men, which subtly enhanced the wearers’ physical appearance. In 1985, Mitterand’s minister of culture Jacques Lang created a scandal by appearing at the National Assembly wearing a black Mugler suit with a Mao collar. Lang responded by praising the designer’s contributions to modern culture.

Thierry Mugler (Left)

Black double-breasted wool bouclé suit with wool sweater, circa 1993, France, The Museum at FIT, 2016.47.8, Gift of Anna CosentinoThierry Mugler (Right)

Man’s dark olive striped wool twill suit, fall 1995, France, 97.116.2, Gift from Mr. Sully Bonnelly -

Image InfoClose

Yves Saint Laurent

Born in Algeria in 1936, when it was still a French colony, Saint Laurent moved to Paris in 1954, the year the Algerian War for Independence began. Persecuted in his youth for being gay, Saint Laurent supported women’s liberation and was among the first French couturiers to design trouser suits.

Haute couture wool twill pinstripe pants suit, spring/summer 1967, France, Lent by Hamish Bowles

-

Image InfoClose

A selection of accessories part one

Accessories have always played a very important part in fashion – and in the Paris fashion system, in particular.

-

Image InfoClose

A selection of accessories part two

From fans and parasols to hats and handbags, accessories complete the look. Many French milliners, such as Caroline Reboux, became world-famous for the hats they designed.

-

Image InfoClose

A selection of accessories part three

Indeed, in the 19th century Parisian milliners were widely regarded as artists and “signed” their creations with labels even before Worth made this the practice among couturiers.

Cult of the Designer

The myth of Paris has heavily emphasized the cult of the designer, a genealogy of genius, whereby Worth begets Poiret who begets Chanel who begets Dior, etc. Yet creativity is not simply a matter of individual talent. Chanel was an extraordinary woman, but, she did not “invent” the Little Black Dress or abolish the corset. Indeed she might today be forgotten if Karl Lagerfeld had not awoken the sleeping beauty at the House of Chanel.

-

Image InfoClose

Cult of the Designer Installation View

Today, many of the world’s most acclaimed designers choose to show their collections in Paris. More importantly, the headquarters of many luxury conglomerates, such as LVMH and Kering, and private luxury fashion companies, like Chanel and Hermès, are based in Paris.

-

Image InfoClose

Chanel was an extraordinary woman, but she did not “invent” the Little Black Dress any more than she abolished the corset. Like every designer, she worked within a particular culture with its own traditions, ideologies, structures, and gatekeepers. In 1920s Paris, a generation of “new” women (including many women designers) welcomed the radical transformation of modern fashion.

Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel (Left)

Black silk crepe haute couture dress with trompe-l’oeil embroidered jewelry, 1983, France, The Museum at FIT, 91.255.9, Gift from The Estate of Tina ChowGabrielle “Coco” Chanel (Right)

Black lace and silk dress, circa 1926, France, The Museum at FIT, 80.13.14, Gift of Mrs. Georges Gudefin -

Image InfoClose

Just as couture clients have always been international, so also have Paris couturiers. Had Elsa Schiaparelli stayed in Rome (where she was born in 1890), she could never have become an internationally-famous fashion designer. Chanel jealously dismissed her as “that Italian artist who makes clothes,” but Schiap was Chanel’s most formidable rival in the late 1930s.

Madame Grès (Left)

Ivory silk jersey gown, circa 1945, France, Lent by Hamish BowlesElsa Schiaparelli (Right)

Black velvet embroidered jacket with sequins and beads, winter 1937-1938, France, Lent by Hamish Bowles -

Image InfoClose

Jacques Doucet

The descendant of silk merchants and manufacturers of lingerie, Jacques Doucet became one of the most famous couturiers of the Belle Epoque. Like Worth, he employed more than 500 people and had an illustrious clientele of European royalty and famous actresses. An art connoisseur and collector, with a particular love of the 18th century, he was also one of the founding members of the Société de l’Histoire du Costume.

Jacques Doucet, Rose and cream brocade dress, circa 1880, France, The Museum at FIT, 2019.1.3

-

Image InfoClose

Christian Dior

From 1947 until his death a decade later, Christian Dior was central to the revival of the Paris fashion system. This rare and important Dior dress was donated to The Museum at FIT by Lauren Bacall. Harper’s Bazaar reported that its “glimmering butterfly print” was designed by the photographer Brassai, and was carried by Henri Bendel. It was featured on the cover of Life, worn by French model Sylvie Hirsch.

Christian Dior, Haute couture gold, printed silk gauze two- piece dress, spring 1951, France, The Museum at FIT, 68.143.20, Gift of Lauren Bacall

-

Image InfoClose

Phoebe Philo for Céline

Phoebe Philo was born in Paris to British parents, but she grew up in London and studied at Central Saint Martins. In 1997, she began working for Chloé, but her greatest impact came during the decade that she designed for Céline. Philo’s minimalist aesthetic and much- copied accessories transformed the French luxury house into a global fashion force. Hedi Slimane took over in 2018, rebranding the house as Celine (without the accent).

Pink silk jersey dress with self-drape cape, spring 2017, France, The Museum at FIT, 2017.19.1 Gift of Céline

-

Image InfoClose

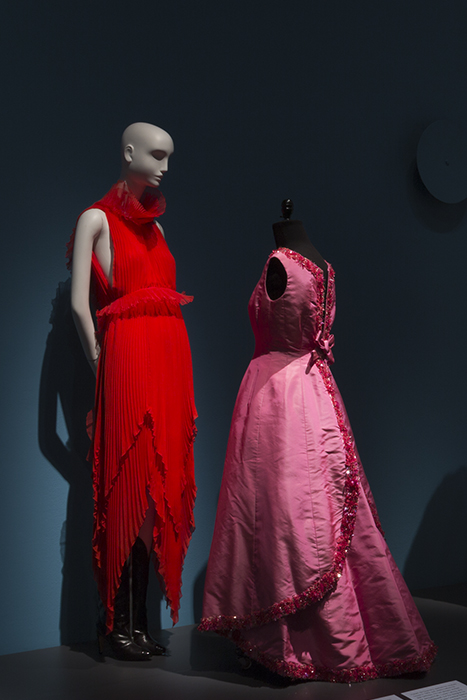

Clare Waight Keller, an English fashion designer, is the creative director of Givenchy, where she succeeded the Italian-born Riccardo Tisci. As Didier Grumbach told Womens Wear Daily: “Paris has changed, the system has changed… For the system to function, the participants have to be international, production has to be international. It’s clear that we no longer can or should be 100% French anymore.”

Claire Waight Keller for Givenchy (Left)

Red silk chiffon dress with kangaroo leather and patent python boots, spring 2018, France, The Museum at FIT, 2019.13.1 Gift of GivenchyGivenchy (Rightt)

Pink silk faille haute couture gown with beaded trim, fall/winter 1964-1965, France, Lent by Hamish Bowles -

Image InfoClose

Karl Lagerfeld for Chloé

Chloé is a French fashion house founded in 1952 by the Jewish Egyptian immigrant Gaby Aghion, who had the vision to offer luxury prêt-à-porter (ready- to-wear). Karl Lagerfeld began designing for Chloé in 1966, and his creations from the 1970s were extremely influential. He returned as creative director of Chloé in 1992 and was followed in due course by Stella McCartney, Phoebe Philo, and now Natacha Ramsay-Levi.

Black and gold embroidered tulle and silk chiffon evening ensemble, fall/winter 1993- 1994, France, Lent by Mrs. John Gutfreund

Fashion, Art, Luxury

In the 20th century, as Paris faced growing international competition, the French increasingly presented the haute couture as the epitome of art and luxury and a part of the unique patrimony of France. Today, many of the world’s most acclaimed designers choose to show their collections in Paris. More importantly, the headquarters of many luxury conglomerates, such as LVMH and Kering, and private luxury fashion companies, like Chanel and Hermès, are based in Paris.

-

Image InfoClose

Fashion, Art, Luxury Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

Jean Paul Gaultier

Jean Paul Gaultier first started presenting couture collections in 1997. For his Spring/Summer 1998 couture show, he drew inspiration from 18th- century French fashion, placing both men and women in “court dresses” like this one. He even created a head-dress in the form of a sailing ship, like one actually worn in the 1770s to celebrate a French naval victory.

Haute couture ensemble, black silk crepe dress and gold lamé overdress with paniers, spring/summer 1998, France, Lent by Jean Paul Gaultier

-

Image InfoClose

Agnès-Drecoll

The Great Depression hit France later than America, but when it did, it damaged the couture badly. Many couture houses folded or had to form alliances with other houses. Agnès- Drecoll, for example, was a couture house founded in 1931 by merging Agnès (Mme Havet, a former employee of Doucet) with Christophe Drecoll (who had previously merged with Beer). The house of Agnès-Drecoll was liquidated in 1933, and briefly revived again in 1937.

Yellow silk satin and rhinestone evening dress, circa 1934, France, Collection of Newark Museum, Gift of Mrs. Wells P. Eagleton, 1940

-

Image InfoClose

Christian Dior

Hamish Bowles recalls finding “this scrunched up black chiffon dress” at a second-hand stall in Paris; “I started to get the chills, and sure enough, I found a tape sewn into the hem,” identifying the dress and indicating that it had been worn by Dior’s “emblematic mannequin” Lucky. Mystère de New York was a very famous dress from Christian Dior’s 1955 Y-line. Harper’s Bazaar described it as “one of the loveliest dresses of his collection, and in all of Paris.”

“Mystère de New York” black haute couture chiffon over silk faille dress, 1955, France, Lent by Hamish Bowles

-

Image InfoClose

Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel

This ravishing evening cape by Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel exemplifies the glamour of Paris fashion between the wars, when the New Woman took center stage. The 1920s and 1930s were a golden age for women designers in Paris. Chanel was the most famous, but her rivals included Schiaparelli, Vionnet, Lanvin, and Alix (later known as Madame Grès). By contrast, the postwar period was dominated by men, such as Dior, Balenciaga, and Fath. Interestingly, today both Chanel and Dior are led by female designers.

Red doubled silk crepe de chine evening cape with feather trim, 1927, France, The Museum at FIT, 96.69.15, Gift from The Dorothea Stephens Wiman Collection