All About Eleanor

Eleanor Lambert established transformative initiatives such as the New York Dress Institute’s Couture Group, the Coty American Fashion Critics’ Awards, biannual Press Week, the International Best-Dressed List, and the Council of Fashion Designers of America. She also promoted causes such as the March of Dimes’ fight against polio by producing fashion shows that brought attention to both humanitarian fundraising and American fashion. Lambert used these ventures as a platform to increase the recognition of American fashion and the public perception of designers such as Geoffrey Beene, Stephen Burrows, Halston, and Valentina.

Featuring objects from The Museum at FIT and FIT’s Special Collections and College Archives, this exhibition explores the impact of the “Empress of Seventh Avenue” through five aspects of Lambert’s career. She played an integral role in several professional organizations. Lambert utilized relationships with political figures, as well as creative society—artists, writers, and socialites—to raise the profile of American fashion. She supported diversity by promoting black fashion professionals. ![]()

-

Image InfoClose

Eleanor Lambert

Photograph by Peter Fink for The Denver Post, August 14, 1961. Reproduction courtesy of FIT Graduate Studies Collection

-

Image InfoClose

BILL BLASS COAT

This Bill Blass coat was donated by Eleanor Lambert to The Museum at FIT. Blass was Lambert’s client and friend, as well as a favorite designer for her personal wardrobe. Lambert often wore clothing designed by her clients in appreciation of their talents and as a show of her support.

Bill Blass, printed linen coat, circa 1970, The Museum at FIT, 79.116.2, Gift of Eleanor Lambert. Photograph © MFIT

Organizations

Eleanor Lambert was a pioneering publicist whose work with various initiatives brought new thinking to the advancement of American fashion. Lambert was hired as the press director for the New York Dress Institute to overhaul their approach to advertising. She would go on to help create the Coty American Fashion Critics’ Awards, Press Week, and the Council of Fashion Designers of America. Lambert continually developed new strategies to bring American designers to the forefront of the industry’s attention. ![]()

-

Image InfoClose

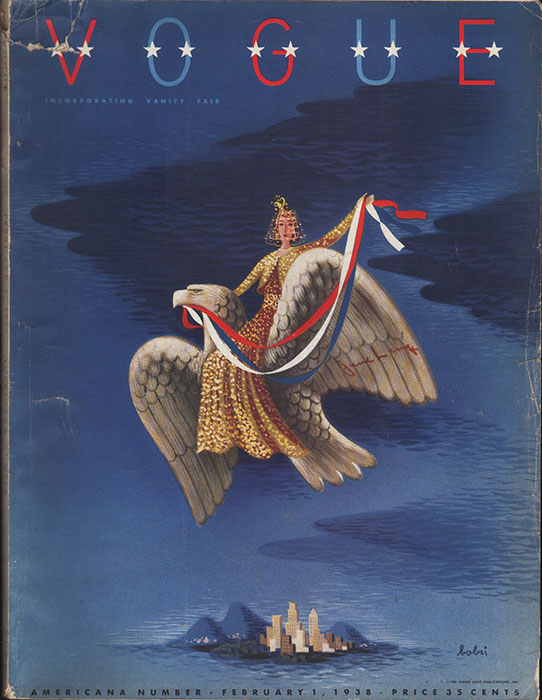

Vogue, 1938

This 1938 issue of Vogue discusses the rising status of American fashion. Paris had long been the reigning capital of fashion. However, during the Nazi occupation of Paris during World War II from 1940 until 1944, the city’s industry was isolated. Lambert saw that as an opportunity to increase the profile of American fashion, and she played a significant part in making that a reality.

Cover of Vogue, February 1938. FIT Graduate Studies Collection

-

Image InfoClose

INSTALLATION VIEW, COTY AWARD EPHEMERA AND HALSTON HAT

In 1942, Eleanor Lambert collaborated with the cosmetics company Coty to produce the Coty American Fashion Critics’ Awards. The awards recognized outstanding American designers as individuals in a period when manufacturers and department stores dominated the industry. A jury of fashion editors voted to select the most influential designers of the year. Halston, one of Lambert’s favorite designers, received the Coty Award in 1962 while working as the head milliner at Bergdorf Goodman. The feathered hat shown here exemplifies his elegant and innovative millinery designs.

Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

INSTALLATION VIEW, COUTURE GROUP PRESS PHOTOGRAPHS

In 1943, Eleanor Lambert began Press Week (later renamed New York Fashion Week) to establish an event for designers to showcase their seasonal collections. A printed photograph of each design in a collection was presented to the journalists and buyers in attendance. These images represent some of the many designers with whom Lambert worked throughout her career.

Press release images from various designers, 1942-1972. Reproductions courtesy of FIT Special Collections and College Archives. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

INSTALLATION VIEW, COUTURE GROUP PRESS PHOTOGRAPHS

Press release images from various designers, 1942-1972. Reproductions courtesy of FIT Special Collections and College Archives. Photograph © MFIT

Fashion Meets Politics

Eleanor Lambert’s work in the fashion industry extended into the political sphere. She used her respected position to enhance the industry’s credibility on the national stage. She helped the fashion industry receive government funding and support through the National Council on the Arts and promoted American designers to public figures such as Jacqueline Kennedy. Lambert produced the first fashion show at the White House in conjunction with President Johnson’s “Discover America” tourism program. She also produced the “March of Dimes Fashion Show,” raising money for the program created by President Roosevelt to fight polio. ![]()

-

Image InfoClose

New York Herald Tribune, 1963

Representing the Council of Fashion Designers of America, Eleanor Lambert testified before Congress in 1963 to help acquire funding for the American fashion industry. Her testimony convinced senators that fashion was one of the arts and therefore qualified to receive funding from the newly formed National Council on the Arts.

“Yes, Fashion Design Is One of Arts,” New York Herald Tribune, April 9, 1963. FIT Special Collections and College Archives

-

Image InfoClose

INSTALLATION VIEW, “DISCOVER AMERICA” SCARF

Eleanor Lambert produced the first fashion show at the White House on February 29, 1968. Titled “Discover America,” it celebrated the American fashion industry by showcasing the work of approximately fifty designers. Frankie Welch created hand-painted promotional scarves that were given to the guests and later produced for the public.

Frankie Welch, “Discover America” printed polyester scarf, c. 1968. FIT Graduate Studies Collection. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

INSTALLATION VIEW, LIFE, 1961

It was politically and economically important to the fashion industry for Jackie Kennedy to wear American labels. Although Oleg Cassini’s designs copied French couture, his brand was American. LIFE’s 1961 “Jackie Look” issue underscored Kennedy’s influence on fashion, emphasizing that women wanted to emulate her style.

Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

GOURMET GALA, 1977

In order to combat the debilitating childhood disease of polio, President Franklin Roosevelt founded the March of Dimes in 1938. Lambert began to collaborate with the foundation in 1944, organizing fundraising fashion shows, securing sponsorship, obtaining the participation of designers, and coordinating publicity. This photo shows how she also participated in other March of Dimes fundraising events, such as the Gourmet Gala.

Eleanor Lambert at the Gourmet Gala, 1977. Reproduction courtesy of March of Dimes

Creative Society

Eleanor Lambert harnessed the celebrity status of artists, dancers, socialites, actresses, and writers to elevate American fashion. Earlier in her career, Lambert had promoted artists and museums, working with the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Costume Institute. In 1949, she commissioned one of her early clients, Salvador Dalí, to design promotional images for the International Silk Association. In 1940, Lambert took over the International Best-Dressed List, moving its base from Paris to New York to celebrate the style of a variety of celebrities, socialites, politicians, and fashion professionals. Impressed by the list’s success, Truman Capote asked for Eleanor Lambert’s guidance in planning his 1966 Black and White Ball. ![]()

-

Image InfoClose

BLACK AND WHITE BALL, 1966

On the day of Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball, Eleanor Lambert was so busy preparing for the event and publicizing her client, celebrity hair stylist Kenneth, that she missed her own hair appointment. She put on her signature turban and hoped to go unnoticed. Unfortunately for her, she entered the ball behind Frank Sinatra and Mia Farrow.

Adolfo, mask and headpiece worn by Marietta Tree to the Black and White Ball, 1966. The Museum at FIT, 91.190.12, Gift of Penelope Tree. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

ELEANOR LAMBERT AND SALVADOR DALÌ

On a commission from Eleanor Lambert, Salvador Dalí designed Surrealist images featuring butterflies and cocoons to re-ignite the purchase of silk in America following World War II. This is one of his designs for the International Silk Association, shown on the Fall 1950 cover of American Fabrics.

Cover of American Fabrics, Fall 1950. FIT Graduate Studies Collection

Black Fashion Support

Eleanor Lambert was an avid supporter of black fashion models, designers, and publications. She hired black models for high profile fashion shows such as the 1959 Moscow Exhibition and the 1973 Versailles Fashion Show, which she organized. She selected her client Stephen Burrows as one of the five designers to represent American fashion at Versailles. Lambert wrote about the designer Jon Haggins in 1972 in her syndicated newspaper column, citing him as the “first black fashion designer to make a name on Seventh Avenue.” In 1961, Lambert’s client Pauline Trigère hired model Beverly Valdes, making her the first black Seventh Avenue fit model. ![]()

-

Image InfoClose

STEPHEN BURROWS JACKET

Stephen Burrows, leather and knit jacket, fall 1970. The Museum at FIT, 92.105.6, Gift of Stephen Burrows. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

STEPHEN BURROWS’ MODELS AT THE BATTLE OF VERSAILLES, 1973

Chicago Tribune, November 26, 1973. FIT Special Collections and College Archives

-

Image InfoClose

INSTALLATION VIEW, SUPPORTING BLACK DESIGNERS AND MODELS

Top Row: Press photograph of Beverly Valdes for Pauline Trigère, Fall 1961.

Eleanor Lambert’s draft of the “She” newspaper column on designer Jon Haggins, 1972.

Portrait of Jon Haggins, 1972.

Bottom Row: “Propaganda Goof Over U.S. Fashions” LIFE, July 27, 1959

Chicago Tribune, November 26, 1973.

All objects from FIT Special Collections and College Archives. Photograph © MFIT

Eleanor Lambert’s Vision of Seventh Avenue

Eleanor Lambert’s vision of Seventh Avenue is represented through this selection of garments designed by a few of her esteemed clients. As well as promoting the New York fashion industry, Lambert advocated for individual designers to receive exposure in the press and name recognition through the labeling of their clothes. Lambert also supported her clients, such as Halston, through challenging moments in their careers. She continually looked towards the future of the fashion industry and its innovative designers. Because of Lambert’s successful work as a publicist and her recognition of talent, many of her clients, such as Calvin Klein, Claire McCardell, and Oscar de la Renta, are still celebrated today. ![]()

-

Image InfoClose

Installation View

-

Image InfoClose

TRAINA-NORELL DRESS

Designer Norman Norell partnered with manufacturer Anthony Traina in a deal that Eleanor Lambert helped to negotiate. Norell was offered more money if his name did not appear on the label, but he chose recognition over financial gain. His name appears on the label of this dress, acknowledging his creative labor in designing for the manufacturer.

Traina-Norell, silk chiffon gauze evening dress, circa 1947. The Museum at FIT, 2001.74.2, Gift of Beatrice Renfield. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

HALSTON DRESS

During the 1972 Coty Awards, Halston shocked many of the attendees with an unorthodox fashion show. He collaborated with Andy Warhol to stage a performance art “happening.” Eleanor Lambert supported Halston amid the negative press, stating “the story was covered in every newspaper in the country…[he] is following Elsa Maxwell’s old adage: ‘I don’t care what you say about me as long as you spell my name right.’”

Halston, polyester jersey evening dress with sequins, 1972. The Museum at FIT, 74.107.30, Gift of Lauren Bacall. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

CALVIN KLEIN COAT

This coat is an original sample that helped launch Calvin Klein’s business in the fall of 1968. Impressed by Klein’s skill for cutting coats without a pattern, Eleanor Lambert took him on as a client. She later called him “one of the most sensational successes of American fashion’s recent history.”

Calvin Klein, wool coat, 1968. The Museum at FIT, 2019.54.3A, Gift of Sheryl and Barry K. Schwartz. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

RUDI GERNREICH PANTSUIT

Rudi Gernreich’s designs were often controversial. For example, when he designed this graphic ensemble, women in pantsuits were uncommon. In 1963, Gernreich designed a similarly radical suit, incorporating mismatched lapels. He won the Coty Award that year, upsetting the established and more traditional designer Norman Norell. Eleanor Lambert’s forward-thinking attitude led her to support Gernreich’s designs.

Rudi Gernreich, cotton and silk pantsuit, resort/spring 1969. The Museum at FIT, 80.227.3, Gift of Mrs. Ruth L. Peskin. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

OSCAR DE LA RENTA CAFTAN

In 1965, Eleanor Lambert recognized Oscar de la Renta’s budding talent and offered to represent him for free. After finding great success, de la Renta hired a private marketing team; however, he sent Lambert checks to repay her for her support. In 1967, the year this caftan was created, the designer won a Coty Award for his trendsetting Russian- and “Gypsy”-themed collections.

Oscar de la Renta, brocaded silk bark cloth caftan with jeweled gold braid, 1967. The Museum at FIT, 79.147.4 Gift of Diana Vreeland. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

GEOFFREY BEENE DRESS

The last fashion presentation that Eleanor Lambert attended was Geoffrey Beene’s September 2003 show, held just after her 100th birthday. Beene was known for his sophisticated yet playful aesthetic. This dress, for example, was designed to resemble a sarong skirt falling off the hip.

Geoffrey Beene, sequin, chiffon, and satin evening dress, circa 1993. The Museum at FIT, 2003.72.1, Gift of Norma Kline Tiefel. Photograph © MFIT

-

Image InfoClose

MAINBOCHER DRESS

This Mainbocher dress was originally designed for Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, a close friend of Eleanor Lambert’s. Simpson was an American divorcee and notorious for her marriage to King Edward VIII, which led to his abdication. She was included on the Best-Dressed List multiple times, creating controversy and tension between members of the British royal family.

Mainbocher, silk crepe evening dress, 1943. The Museum at FIT, 75.119.6, Gift of Edith D’Errecalde-Hadamard. Photograph © MFIT